JENNIFER KILGORE-CARADEC

Keywords

Modernist Poets, World War I, May Weddenburn Cannan, Vera Brittain, May Sinclair, Mary Borden, Charlotte Mew, Louise Imogen Guiney, Florence Earle Coates, Eleanor Farjeon, Edith Wharton, Nancy Cunard, Eva Dobell, Lady Margaret Sackville, Constance Renshaw, Anna Wickham, Harriet Monroe, Alice Corbin, Edith Sitwell, Gertrude Stein, H.D., Carola Oman

Abstract

This paper begins factually by discussing how women modernists were late recognised, and women poets of war received even less attention. The centenary of World War I could have changed that, and certainly began a more balanced discussion of the matter. The paper ends meditatively, noticing that the most effective poems to explore the horrors of war and promote the stability of peace, by women as well as men, do so by employing a longer angle with regard to past conflicts.

Resumé

Les écrivaines de l’avant-garde anglophone ont eu une reconnaissance tardive, à partir de la deuxième moitié du vingtième siècle, et les femmes poètes de guerre ont reçu encore moins d’attention. Le centenaire de la première guerre mondiale a permis de commencer à ré-équilibrer la situation pour les écrivaines de la guerre. Cette discussion se termine de façon méditative, considérant comment les femmes, ainsi que les hommes, utilisent l’histoire ancienne pour parler du prix humain des conflits, pour promouvoir la paix.

_______________

Women Writing Their Time during World War I

What we know of women modernists today is largely thanks to the transmission that women who study literature have provided. In their early critical writing, Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot intentionally or unintentionally wrote Edith Sitwell, Virginia Woolf, Dorothy Richardson, and Gertrude Stein out of the story, even while Eliot was on friendly terms with both Woolf and Sitwell. Rare are the men that have chosen to focus on the women who write modernism. While the recent (and only satisfactory) anthology, Modernist Women Poets (2014) was edited by Robert Hass and Paul Ebenkamp, no monograph-length work about the poetry written by women during and concerning World War I has yet had a male author. In such a context, honorable mentions should perhaps be discerned to anthologists who have included women more than minimally or critics who have spoken about women’s war writing. Jon Silkin (1930-2011) was the first to include five women poets alongside the poets who fought in combat in the third edition of The Penguin Book of First World War Poetry in 1996 (Haughton 437). Special mention can be discerned for other anthologies of war poetry by men that have included poems by women, such as John Stallworthy’s Oxford Book of War Poetry (1984), Dominic Hibberd and John Onions’s The Winter of the World: Poems of the great War (2007), and Tim Kendall’s Poetry of the First World War (2013). Several critical studies deserve accolades as well, such as The Great War and the Language of Modernism(2003) by Vincent Sherry, which speaks in great length about Virginia Woolf. Unsurprisingly, women are ranked among the best critics of war poetry, and one can only regret that the very astute Edna Longley in Poetry in the Wars (Bloodaxe, 1986) devotes no chapter to poetry by women.[1]

Remembering the poets of World War I during the centennial was constructive, provided that women had their place. The war was deadly, and many poets transmitted that very essence of war: death. Commemorating the period when the average loss of life amounted to 6000 people a day, is complex—no one alive now remembers what it was like. How can we connect with the statistics themselves? In a three-day period between August 20-23, 1914, around 40,000 people were killed. Beyond the tragedy of so much loss of human life (and its corollary in human creativity), there was also the urgent physical complication of what to do with so many decomposing bodies. At the beginning of the war, between August and November of 1914, the French suffered 2,737 deaths from war each day. Some days, of course, fewer people were killed. French casualties were highest throughout the war, but the British too were heavily affected. During the years 1914-1918, the British are said to have lost on average, 457 soldiers a day. Of course these kinds of losses take their toll not only on loved ones directly affected, but also on other civilians and soldiers too.[2] It is worth remembering that during World War I, the front page of the Times featured the day’s casualty and missing list.

The memorial monument for British war poets in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey, lists sixteen of them.[3]Five of the poets died in battle in 1914, and many of the others were killed before the war ended in 1918. The sixteen names surrounded by the Wilfred Owen quotation, carefully carved into the stone slab by Harry Meadows, were intended to symbolically represent all war poets of World War I, according to Westminster Abbey’s website.[4] Despite its attractive minimalist beauty, the inherent danger of such a monument is that we might forget that there were much greater numbers of other war poets who died as soldiers in World War I.[5] Yet in contrast to the French Pantheon’s 1927 list of 560 writers of all nationalities that died in France during World War I, the list of sixteen names of British war poets seem to invite the onlooker to read their works.

However the Westminster Abbey monument, consecrated in 1985 in the presence of Britain’s poet laureate Ted Hughes, features the names of no women,[6] despite the fact that many women alive at the time wrote poetry about World War I and had already been the object of literary critical studies. For the record’s sake, here are a few of them (this list includes women of all nationalities, writing in English):

Marian Allen, Lilian M. Anderson, Pauline Barrington, Madeline Ida Bedford, Maud Anna Bell, Nora Bomford, Matilda Barbara Bentham-Edwards, Mary Borden, Sybil Bristowe, Vera Mary Brittain, May Wedderburn Cannan, Isabel C. Clark, Florence Earle Coates, Margaret Postgate Cole, Mary Gabrielle Collins, Alice Corbin, Nancy Cunard, Elizabeth Dariush, Helen Dircks, Eva Dobell, Helen Parry Eden, Gabrielle Elliot, Eleanor Farjeon, Gertrude S. Ford, Elizabeth Chandler Forman, Lilian Gard, Muriel Elsie Graham, Rosaleen Graves, Nora Griffiths, Diana Gurney, Cicely Hamilton, Helen Hamilton, Ada M. Harrison, Mary H.J. Henderson, Agnes Grozier Herbertson, May Herschel-Clarke, Teresa Hooley, Elinor Jenkins, Anna Gordon Keown, Margery Lawrence, Winifred Mabel Letts, Olive E Lindsay, Amy Lowell, Rose Macaulay, Nina Macdonald, Florence Ripley-Mastin, Charlotte Mew, Alice Meynell, Luther Comfort Mitchell, GM Mitchell, Harriet Monroe, Edith Nesbit, Eileen Newton, Eleanor Norton, Carola Oman, May O’Rourke, Emily Orr, Jessie Pope, Margaret Postgate (Dame Margaret Cole), Inez Quilter, Dorothy Una Ratcliffe, Ursula Roberts, Lady Margaret Sackville, Aimee Byng Scott, May Sinclair, Edith Sitwell, Cicili Fox Smith, Marie Carmichael Stopes, Muriel Stuart, Mary Stud, Millicent Sutherland, Sara Teasdale, Lesbia Thanet, Aelfrida Tillyard, Iris Tree, Alys Fane Trotter, Katharine Tynan, Viviane Verne, Alberta Vickridge, Mary Webb, M. Winifred Wedgwood, Catherine Durning Whetham, Lucy Whitmell, Margaret Adelaide Wilson, Marjorie Wilson…

The names above represent a small, more visible, portion of the totality. Sarah Montin cited Catherine Reilly in her 2015 doctoral thesis, noting that 2,225 poets wrote about the period of World War I and 552 of them were women.[7] The poet Lucy London has devoted considerable energy to preserving their memories with Female Poets of the First World War(volume 1 in 2013, and volume 2 in 2016). Some have argued, during the war as now, that women were not soldiers, and did not have real experience of battle. Nonetheless they were in some cases eyewitnesses of the front. They too participated in the war effort and often wrote extremely moving testimonial poetry about the conflict. Factual concrete knowledge of war was also what they experienced while at the home front. To better illustrate this point, let us consider the woman who stays at home during the war, and continues in her daily civilian pursuits with relatively little change to her normal routine. One day she goes to a film and sees a news broadcast before the film starts or a film about the war… and so she writes:

A War Film

I saw,

With a catch of the breath and the heart’s uplifting,

Sorrow and pride, the ‘week’s great draw’ —

The Mons Retreat;

The ‘Old Contemptibles’ who fought, and died,

The horror and the anguish and the glory.

As in a dream,

Still hearing machine-guns rattle and shells scream,

I came out into the street.

When the day was done,

My little son

Wondered at bath-time why I kissed him so,

Naked upon my knee.

How could he know

The sudden terror that assaulted me? . . .

The body I had borne

Nine moons beneath my heart,

A part of me . . .

If, someday,

It should be taken away

To War. Tortured. Torn.

Slain.

Rotting in No Man’s Land, out in the rain —

My little son . . .

Yet all those men had mothers, every one.

How should he know

Why I kissed and kissed and kissed him, crooning his name?

He thought that I was daft.

He thought it was a game,

And laughed, and laughed.

This is Teresa Hooley (1888-1973), on the British reconstructed drama-documentary by H. Bruce Woofe, the film Mons(1926) about the August 1914 British retreat from Belgium. The poem was published in Hooley’s book, Songs of All Seasons (London, 1927). The speaker of the poem, should not of course be confused with the author, but it gets more complicated: Teresa Hooley was not the poet’s real name. It was only a pen name. In the real world she was called Mrs. Frank Butler and lived a relatively uneventful life in Derbyshire. But that’s just the point, isn’t it? She did not go to the front and take part in the mud and death that made History with a capital H. Her story would be instead about taking care of children: a gentle and quiet story about domestic lives—after the war, and in a time of peace…. yet still, and ever after, affected by the war.

“A War Film” checks all of the wrong boxes in the check lists from the early 20th century to discern what so called “valid” war poetry is. It is a poem about war written by a woman, written by someone who never went to the front, someone with an invented name, someone who cannot properly memorialize with no actual documentary footage, but mere reconstructions of the scene (there was no documentary film made about the battle of Mons 1914 as it was happening: people were too busy dying to turn movie reels). Nonetheless, the point that this poem so amply illustrates is that anyone who is a thinking person is affected by war, whether or not they are actually participating in it.[8] Peaceful lives and activities are affected. Women during war time became widows or lost sons. That is horrific first-hand experience of what war is, and that alone should have justified larger boundaries about what war poems could be. Even W.B. Yeats, who often spoke out against war poetry, still decided to write an elegy, “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory,” for Lady Gregory’s son, who died at the front in February 1918.[9]

Chronologically speaking, from 1914-1918

Only toward the end of the twentieth century, from approximately the late 1970s, following on the heels of the women’s liberation movement, did women’s poetry about World War I very slowly come to be recognized as authentic poetry of testimony about the war and the war period.[10] This was quite late recognition, given that a number of women were eyewitnesses and actors in the conflict, as nurses, ambulance drivers, medical aids, and “munitionettes,” that is, women working in arms factories, who were often called “canary girls” when their skin began to turn yellow, due to the toxicity of the products they were handling, such as TNT, cordite, and sulfuric acid.[11] Estimates of the number of British munitionettes vary: perhaps there were 212,000 women working in British arms factories in 1914, with numbers increasing to 950,000 by the end of the war.[12] It is telling that these British Women factory workers wore metal identity disks around their necks, just like British soldiers. During air raids, such factories would be the enemy’s prized targets, but they were subject to internal explosions as well, as in Silvertown in 1917 (73 casualties, 400 wounded) and Chitwell in 1918 (130 casualties), or the fire of Nov 20, 1917 (3 deaths) and explosion of March 1918 (3 deaths) at the HM factory in Langwith. But those losses of life were often hushed. The details of the explosion on December 5, 1916 that killed 35 women and wounded many more at the Barnbow National Filling Factory in Leeds were kept secret until well after the war was over, whereas in 2016 a decision was taken to make the site a national historic monument.[13] The contrast is clear enough: soldiers dying on the front were immediately recognized. Women dying while producing arms have only begun to receive mainstream public attention a century later.[14] One may envision that the situation with regard to the recognition of women’s contribution as well as women’s working accidents in the United States was somewhat similar, even if the U.S. entered the war later. Who spoke about the exponential rise of women employed at the Colt Factory of Harford, Connecticut as the war trudged on? Colt employed 43,380 women in 1913, and 86,991 in 1917, as young American men were drafted into service.[15]

Catherine Reilly’s anthology of women’s poetry from the First World War, Scars Upon My Heart (1981) largely contributed to the current reevaluation of poetry written by women during World War I. One may wonder why this recognition came so late—and why it continues to be so late in coming. as Stacy Gillis noted, writing in The Oxford Handbook of British and Irish War Poetry in 2007, “the poetry of the First World War…was, from the opening shots of the war until the 1980s, considered a masculine group enterprise” (101). Simon Featherstone added:

There persists a lack of attention to women’s poetry of both wars, despite the recovery and revaluation of a range of women’s prose writing from these periods. In the present collection, for example, only two essays concentrate solely on women writers, and that imbalance is typical of the field. Whilst Virginia Woolf, Vera Brittain, Rebecca West, Elizabeth Bowen, Rose Macaulay, and other writers of fiction and autobiography are securely placed in any account of First and Second World War writing, no comparable figure has emerged as a representative female war poet. (445).

With so many women acting in roles that took them close to the front or forced them to risk their safety at home, it was inevitable that poets would be involved, or that the shock of the moment would turn women into poets. Carola Oman, May Weddenburn Cannan, Mary Borden and Vera Brittain served as nurses to soldiers. May Sinclair was an ambulance worker. Nina MacDonald, Madeline Ida Bedford, and Mary Gabrielle Collins were munitionettes. Other poets, such as Charlotte Mew, occupied the home front, which was also fraught with numerous personal difficulties further aggravated by the war, with its financial strains and shortages. Margaret Postgate Cole campaigned against conscription, and Ford Madox Ford in Parade’s End characterized her as a “hot pacifist” in the person of Valentine Wallop (Kendall, Poetry of the First World War, 175).

Given their involvement both directly linked to the conflict and through poetic composition, why are so few of women’s works studied when one studies poetry about war? Gillis postulated that Elaine Showalter’s A Literature of their Own (1977) and Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s The Madwoman in the Attic (1979) were instrumental starting points for “the gendered reconsideration of literary history, broadening its perspective to include women’s writing” (104). Could there be a legitimate justification for the public’s collective neglect to read women, such as that poetry written by women during World War I might be stylistically inferior to that written by men? Must the lack of study of women’s poetic texts about World War I be linked to the reasons why women were, and still are not, fully perceived as actors in armed conflicts?

Although the mainstream approach (until most recently) to these questions may have been that women do not bear valid testimony about the war, that is simply not true. Women, like men, have been writing about war for centuries, and both genders have been known to write in support of the dominant propaganda, or to write to try to stem or block its flow. Both women and men have composed powerful poems aimed at promoting peace. Hugh Haughton writes of Reilly’s anthology: “Arranged by author rather than theme, the anthology brings back many of the female figures from the wartime anthologies later airbrushed out” (438). Airbrushed out is an appropriate image…. so now let us attempt to airbrush the women poets of World War I back into the picture.

As the events leading up the start of World War I were occurring, the link between Emily Dickinson’s poetry and the American Civil War was not yet understood, but even so, all poetic composition arises from a particular context.[16]Women who wrote poetry about war during the First World War would of course know a few things about the generation of poets that had preceded them. That is why one might first consider how war was being portrayed in poetry by women in the several decades that preceded World War I. One can find cases where women’s poetry was taking the long historical perspective even before World War I began. And so, in one of her poems called “Romans in Dorset,” Louise Imogen Guiney (1861-1920) imagined images of the eyes and mouths of the warriors that seem in retrospect oddly prophetic: “In ovals of wan light / Each warrior eye and mouth.” (Guiney, 16).

As soon as Great Britain entered the war on August 4, 1914, the very same week poems were already appearing to encourage soldiers to volunteer. On August 8 The Times published Robert Bridges’s poem “Wake Up England,” which advocated the defense of the nation, “To beauty through blood,” calling pacifists to enlist, “Up careless awake! / ye peacemakers fight!” (see Hibberd and Onions, 3). On September 2, the British Ministry of Propaganda, C.F.G. Masterman, asked famous writers to a meeting at the Ministry of Information to enroll them in a propaganda program. They signed a declaration of writers to support the war effort which was published by the papers under the title: “Britain’s Destiny and Duty: Declaration of Authors: A Righteous War” in the Times (September 18, 1914), and then, “Famous British Authors Defend England’s War” in the New York Times (October 18, 1914). The authors who signed the declaration included Hardy, Wells, Chesterton, Newbolt, Bridges, and Zangwill. Five women writers also signed this document: Jane Ellen Harrison, May Sinclair, Flora Annie Steel, Mary Ward, and Margaret Woods.

The first anthologies of war poems published in Great Britain in 1914 promoted this type of unquestioning patriotism. Patriotic verses would continue to appear, such as The Fiery Cross (1915), edited by Edward and Booth, where one finds such poems as “The Knitting Song” by Jessie Pope (1868-1941), which transforms even domestic gestures like knitting into patriotic actions. Pope promoted the nation’s cause, getting young men to enlist, in poems published in the Daily Mail and the Daily Express and then in her War Poems (1915), More War Poems (1915) and Love on Leave (1919). Rose Macauley’s poem “Many Sisters to Many Brothers” expressed a desire to fight alongside men, declaring in the final line of the poem that for her, because she must stay home, knitting, “a war is poor fun” (qtd. Roberts, 88). Jessie Pope, Matilda Bentham-Edwards, Rose Macaulay, Winifred Mabel Letts, and other women writing poetry at this time fully supported the war effort. In some cases, they were aptly talented writers, and they did what they perceived to be the right thing. With the vantage point of hindsight, they, like Rupert Brooke, probably deserve the benefit of some tolerant interpretation, since the complexities of history are easier to sort out well after the facts. No one should too hastily judge women who chose to cooperate with the British Ministry of Propaganda effort or support the popular nationalist cause for the war. However once that said, it should also be acknowledged that the majority of women writing about World War I ventured to write more truthfully about the horrifying realities of war and its consequences.

May Sinclair (1863-1946), a suffragette, novelist, and poet, was fifty-one years old when the war broke out, yet despite her age she chose to go to the front for three weeks in September 1914 to help the nurses who were tending to wounded soldiers. Working close to the battle she was able to observe first-hand the kind of excitement that the war created and that she would express in her Journal of Impressions in Belgium (1915), where she admitted that reflection diminished and was transformed into ecstatic excitement the closer one got to the line of combat (see Kendall 16). In her poem “Field Ambulance in Retreat,” she describes their bloody cargo: “And, where the piled corn-wagons went, our dripping Ambulance carries home / Its red and white harvest from the fields.” In a poem composed in March 1915, “Dedication (To a Field Ambulance in Flanders)” Sinclair expresses a regret that is shared with other women, concerning the differences in involvement in the conflict between men and women. She regrets that she could not become a soldier, and this fact will be used by some men to suggest that women should have nothing at all to say about the war:

I do not call you comrades,

You, who did what I only dreamed.

Though you have taken my dream,

And dressed yourselves in its beauty and its glory,

Your faces are turned aside as you pass by.

I am nothing to you,

For I have done no more than dream.

While some women were speaking out loudly and clearly for patriotism that wanted nothing less than the departure of all men between the ages of 20 and 40, even to the sacrifice of their lives (after all, that was the most common conception of Patriotism during this time period), others were much more reticent, even at the very start of the conflict. No doubt there were more vocal reticent feminine voices than masculine ones. This was for evident reasons: women did not undergo the same social pressure to get to the front at the beginning of the war, and they could not become soldiers. Nobody would ever hand them a white feather to signify cowardice in public.

Florence Earle Coates (1850-1927), an American visiting England wrote “War,” a poem published in the Athenaeum (August 8, 1914) to denounce war, pictured in the poem as a medusa: “Medusa-like, I seem to see her there — / War! with her petrifying eyes astare —”. In Chicago, though physically quite far from the conflict, Harriet Monroe and Alice Corbin, who are today famous for having published the first great modernist poems in Poetry, A Magazine of verse, devoted an entire issue of the magazine to war poetry where they featured the winning poems of the war poetry contest that had been announced in the September 1914 issue of the review. It gave ample material for the November 1914 issue, which discerned the prize for the best war poem to the relatively unknown Louise Driscoll (see Kilgore-Caradec 2010). Many of the war poems in that issue were written by women and the majority of those poems clearly promoted peace.

Meanwhile, in Britain, Edward Thomas had understood the propaganda tone of many of the poems he had seen, and his personal manifesto was to write against that kind of rhetoric. In December in an article in Poetry and Drama he explained:

The demand is for the crude, for what everybody is saying or thinking, or ready to begin saying or thinking. I need hardly say that by becoming ripe for poetry the poet’s thoughts may recede far from their original resemblance to all the world’s, and may seem to have little to do with daily events. They may retain hardly any color from 1798 or 1914, and the crowd, deploring it, will naturally not read the poems. (342)

As if in response, Eleanor Farjeon, who was romantically involved with Edward Thomas on at least a platonic level, matched that eloquence with a sonnet that speaks of his departure after he enlisted (1915):

Now that you too must shortly go

Now that you too must shortly go the way

Which in these bloodshot years uncounted men

Have gone in vanishing armies day by day,

And in their numbers will not come again:

I must not strain the moments of our meeting

Striving for each look, each accent, not to miss,

Or question of our parting and our greeting,

Is this the last of all? is this—or this?

Last sight of all it may be with these eyes,

Last touch, last hearing, since eyes, hands, and ears,

Even serving love, are our mortalities,

And cling to what they own in mortal fears:—

But oh, let end what will, I hold you fast

By immortal love, which has no first or last. (1915).

Charlotte Mew (1869-1928) who first was recognized with her book The Farmer’s Bride (1916, 1921), in poems such as “May 1915” and “June 1915,” noted that the seasons of spring and summer, usually associated with renewal and hope, were now on the contrary times of separation from life, in an alternative season that war had induced: “What’s little June to a great broken world with eyes gone dim / from too much looking on the face of grief, the face of dread?” Her best-known poem about the conflict is “The Cenotaph” (1919), beginning:

Not yet will those measureless fields be green again

Where only yesterday the wild sweet blood of wonderful [youth was shed;

There is a grave whose earth must hold too long, too deep a [stain,

Though for ever over it we may speak as proudly as we tread.

But there is no glory to transcend the losses that war brings. The end of the poem focuses on a market that takes place next to the memorial monument:

Who’ll sell, who’ll buy

(Will you or I

Lie each to each with the better grace?)

While looking into every busy whore’s and huckster’s face

As they drive their bargains, is the Face

Of God: and some young, piteous, murdered face.

In 1916 Edith Wharton brought out The Book of the Homeless, a collection of poems, prose and artistic reproductions, turning over any money made from the book to helping war refugees in Belgium. Wharton wrote a poem, “The Tryst,” for inclusion in the volume. It presented a dialogue between a woman and a refugee, who explained:

They shot my husband against a wall,

And my child (she said), too little to crawl,

Held up its hands to catch the ball

When the gun-muzzle turned its way.

Nancy Cunard (1896-1965) wrote several powerful poems about the conflict, particularly those published in the first Wheels (1916) anthology, edited by Edith Sitwell. The title for the anthology series was actually taken from Cunard’s poem “Wheels,” which was reproduced in full at the beginning of the 1916 anthology.

I sometimes think that all our thoughts are wheels

Rolling forever through the painted world,

Moved by the cunning of a thousand clowns

Dressed paper-wise, with blatant rounded masks,

That take their multicolored caravans

From place to place, and act and leap and sing,

Catching the spinning hoops when cymbals clash.

And one is dressed as Fate, and one as Death,

The rest that represent Love, Joy and Sin,

Join hands in solemn stage-learnt ecstasy,

While Folly beats a drum with golden pegs,

And mocks that shrouded Jester called Despair.

The dwarves and other curious satellites,

Voluptuous-mouthed, with slyly-pointed steps,

Strut in the circus while the people stare.—

And some have sober faces white with chalk,

And roll the heavy wheels all through the streets

Of sleeping hearts, with ponderance and noise

Like weary armies on a solemn march.—

Now in the scented gardens of the night,

Where we are scattered like a pack of cards,

Our words are turned to spokes that thoughts may roll

And form a jangling chain around the world,

(Itself a fabulous wheel controlled by Time

Over the slow incline of centuries.)

So dreams and prayers and feelings born of sleep

As well as all the sun-gilt pageantry

Made out of summer breezes and hot noons,

Are in the great revolving of the spheres

Under the trampling of their chariot wheels.

In this poem certain images evoke a carnaval, and social distractions in civilian society that seem to exist primarily so that everyone will forget what is simultaneously taking place at the front. In “Destruction” the first lines are more direct: “I saw the people climbing up the street / Maddened with war and strength and thought to kill”. Next to Cunard’s poems are those of Sitwell, who is better known for her magnificent poems about the Blitz of World War II. Here her early talent is evident with “Processions,” where the war has invaded every aspect of life[17]:

The sounds seemed warring suns; and music flowed

As blood; the mask’d lamps showed

Tall houses, light had gilded like despair:

Black windows, gaping there.

Much less known is the poet Eva Dobell (1876-1963) who wrote: “In a Soldier Hospital 1: Pluck” where the first stanza presents the subject who fears the moment when his wounds will be washed:

Crippled for life at seventeen,

His great eyes seem to question why:

With both legs mashed it might have been

Better in that grim trench to die

Than drag maimed years out helplessly.

Vera Brittain, who worked as a nurse, wrote of the war hospital as a sanctuary for her dead love where other soldiers await her care in “Hospital Sanctuary” (1918): “The dim abodes of pain wherein they languish / Offer that peace for which at last you pray” (Hibbered and Onions, 248).

The important contribution by Lady Margaret Sackville (1881-1963) in 1916 was her book The Pageant of War, where she wrote poetry of testimony not only about soldiers, but for all of the dead, including non-combattants and refugees. In more than sixty pages, she captured her time, with poems such as “Flanders 1915,” “The Pageant of War,” “Victory,” “Quo Vaditis?” and “Nostra Culpa,” among others. She gave Siegfried Sassoon the volume as a gift while he was staying at the military hospital Craiglockart in Edinburgh. Wilfred Owen also had a copy of the book and praised Sackville in a letter to his mother (2 octobre 1917).

Constance Renshaw (1891-1964) published England’s Boys (1916), a collection of poems containing “The Great Push (July 1, 1916),” a poem that showed the courage of the troops in a patriotic vein. In another register, “The Fired Pot”(1916) by Anna Wickham (1883-1947) spoke about the brief relationship of a woman with a passing soldier. In “The Vision” published in her collection The Holy War (1916), Katherine Tynan (1859-1931) tells the ballad of a captain who was blinded when he risked everything to put flowers on the tomb of his close friend who was gassed.

Mary Borden (1886-1968) was one of the women who participated in the Battle of the Somme — see her “At the Somme”. She went there to be a nurse, with no previous experience, and in January 1915, she decided to start a hospital under French authority. Borden was independently wealthy from her inheritance, and had then married a British missionary, followed by a British general (according to Hibberd and Onions). In October 1916, she began another hospital at Bray-sur-Somme, which she described in a poem composed in 1917 but that was not published immediately. Her collection of writings about the battle, in verse and in prose, is found in The Forbidden Zone, which was censured in 1917 and would only appear over a decade later when finally published by Heinemann in London in 1929. The poem “The Song of the Mud” vividly describes how the men sank into it, in extremely expressive language (here from the fourth stanza):

This is the hymn of mud-the obscene, the filthy, the putrid,

The vast liquid grave of our armies. It has drowned our men.

Its monstrous distended belly reeks with the undigested dead.

Our men have gone into it, sinking slowly, and struggling and [slowly disappearing.

Our fine men, our brave, strong, young men;

Our glowing red, shouting, brawny men.

Slowly, inch by inch, they have gone down into it,

Into its darkness, its thickness, its silence.

Slowly, irresistibly, it drew them down, sucked them down,

And they were drowned in thick, bitter, heaving mud.

Now it hides them, Oh, so many of them!

Under its smooth glistening surface it is hiding them blandly.

There is not a trace of them.

There is no mark where they went down.

The must enormous mouth of the mud has closed over them.

This is a strong poem of witness, a poem of an eyewitnesses, and it adequately demonstrates that the poetry of a non-combatant woman at the front can be as moving and accurate a poem of testimony as that written by a male soldier. So it is that Mary Borden’s poem “Unidentified” was described by Hibberd and Onions as “in the style of Whitman,” describing “A French Poilu, recognizably akin to the soldiers in Henri Barbusse’s Le Feu” (204). Other examples of excellent testimonial poems by women include “The Armistice” (1918) and “Women Demobilized” (date uncertain) by May Weddenburn Cannan (H & O, 255, and 274).

In fact, we might observe that, to borrow and spin a cliché, behind every man there is a woman. For the male patriot poet like Rupert Brooke (or even the poems of Hardy and Bridges in 1914), you have a Jessie Pope or a S. Gertrude Ford. For the pacifist poet, such as D.H. Lawrence, you have Louise Driscoll, Harriet Monroe, Alice Corbin, or Marion Patton Waldron, whose pacifist poem “Victory” was published in Century (July 1917). Waldron portrays the lover who returns an invalid, whose body becomes a child for the couple, “yes, our child, our child” (qtd. Pollen and Woods, 158). For the poets of witness who participated in the combat such as Sassoon, Owen, Rosenberg, and Gurney, there is Mary Borden giving an eyewitness account of the mud or Nina MacDonald, Madeline Ida Bedford, or Mary Gabrielle Collins writing about being Munitionettes.[18]

Just as many trench poets evoke the beauty of nature found in the larks or the poppies that they observe daily, so women writers of this period were also keen to capture the beauty of nature, with nature being a kind of reminder of the beauty and steadfastness of the will to live, of a life force that might transcend even the carnage of the war, such as Margaret Postgate Cole’s “The Falling Leaves” (November 1915, qtd. Roberts 212). Or nature is a beauty nostalgically recalled in a state of pre-war innocence as Alice Meynell portrayed it in “Summer in England, 1914” (qtd Gillis 109), or as Rosalyn Graves, Robert Graves’s sister, wrote about it in “The Smells of Home” (Hibberd and Onions, p. 258-9). Like male poets, women poets sometimes used images of the cross, be it the military cross or Christ’s cross, to justify the ultimate sacrifice. This is the case in Vera Brittain’s “To My Brother” in which the wounded brother’s medal, “That cross you won / Two years ago” shines “silver in the summer morning sun,” and the brother in the last stanza of the poem is encouraged to “endure to lead the Last Advance” (Roberts, 213).

The Long Angle

The long angle, or as Richard Eberhart might say, “the long reach,”[19] allows poets and readers to gain added perspective and intelligence about war. It brings to bear a far longer historical perspective, and was effectively used by poets trying to capture the reality of warfare. The most effective poems promoting peace often use this long angle. Alice Corbin manages it with word play between times and Time in the last line of “The Great Air Birds Go Swiftly By” (published in Poetry, July 1917):

The great air birds go swiftly by,

Pinions of bloom and death;

And armies counter on shell-torn plains

And strive, for a little breath.

Pinnacled rockets in the gloom

Light for a little space

A gasping mouth, and a dying face

Blackened with night and doom—

As if in a little room

A sick man laid on his bed

Turned to his nurse and questioned when

Mass for his soul would be said.

Life is no larger than this,

Though thousands are slaked with lime,

Life is no larger than one man’s soul,

One man’s soul is as great as the whole,

And no times greater than Time.

The poem may be read about World War I, or could as well be read about a war of antiquity: the birds are birds, dropping seeds, before they are planes dropping bombs. In fact there is little in the poem to situate it firmly only in the period of 1914-1917. This reads as poetry of testimony combined with memory, yet Corbin herself was never actually at the front, being based in Chicago. However, at the time this poem was published, American soldiers were being drafted and sent to the France. Perhaps that is why in the same issue of Poetry, Vachel Lindsay’s poem “Mark Twain and Joan of Arc” was also featured, with Joan becoming a figure of American patriotism, even as Lindsay concluded his poem, “But I, I can but mourn, and mourn again / At bloodshed caused by angels, saints, and men.” (Lindsay 175).

Earlier in this paper, Louise Imogen Guiney’s 1909 poem, “Romans in Dorset” was quoted, as it presented very interesting images of warriors. This poem appeared in Guiney’s collection Happy Endings (1909). Even as it takes a long historical perspective, retracing the history of Dorset, it is also prophetic in its imagery. Such telescoping of history was easier to perform by those who had some knowledge of Latin and Greek and who were aware of ancient history. One finds this technique at work in the best poetry about war that promotes peace, such as Robert Graves’s “Goliath and David” (1916), Isaac Rosenberg’s “Break of Day in the Trenches” (1916), Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est” (1917), Ivor Gurney’s Severn and Somme (1917), David Jones’s In Parenthesis (1937), or later, about the London Blitz in World War II, with Edith Sitwell’s “Still Falls the Rain” (1940), and H.D.’s Trilogy (1944-46). In such poetry, allusions and anachronisms from the past are used to heighten the reader’s comprehension of the cost of war.

So, Carola Oman (1897-1978) who worked for the Red Cross on the Western Front from 1916-1919, evoked her daily unending repetition in “Unloading Ambulance Train,” asking, “Is it an ancient chanty won from some classic shore?” (Hibberd & Onions, p.266), implying that the wounded she was treating were those who perhaps had fought the Punic wars.

Bibliography

Baker, Kenneth. The Faber Book of War Poetry. London: Faber, 1996.

Eberhart, Richard and Rodman, Selden (eds). War and the Poet: An Anthology of Poetry Expressing Man’s Attitudes to War from Ancient Times to the Present. New York: The Devin-Adair Company, 1945.

Featherstone, Simon. “Women’s Poetry of the First and Second World Wars” in Tim Kendall (ed). The Oxford Handbook of British and Irish War Poetry. Oxford: OUP, 2007, 445-460.

Ferrere, Alexandre. “Variations Poétiques sur la Mort” M2 Thesis, Université de Caen, 2017.

Gillis, Stacy, “‘Many Sisters to Many Brothers’: The Women Poets of the First World War” in Tim Kendall (ed). The Oxford Handbook of British and Irish War Poetry. Oxford: OUP, 2007, 100-113.

Guiney, Louise Imogen. Happy Ending: The Collected Lyrics. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1909.

Haughton, Hugh. “Anthologizing War” in Tim Kendall (ed). The Oxford Handbook of British and Irish War Poetry. Oxford: OUP, 2007, 421-444.

Hass, Robert and Ebenkamp, Paul (eds). Modernist Women Poets, An Anthology. Berkeley, California: Counterpoint, 2014.

Hibberd, Dominic and Onions, John (eds). The Winter of the World: Poems of the First World War. London: Constable, 2007.

Hooley, Teresa. Songs of All Seasons. London: Jonathan Cape, 1927.

Kendall, Tim (ed). Poetry of the First World War: An Anthology. Oxford: OUP, 2013.

_______ (ed). The Oxford Handbook of British and Irish War Poetry. Oxford: OUP, 2007.

Kilgore-Caradec, Jennifer, “Les poètes face à la guerre de 1914 : quand la neutralité semble impossible,” I. Bockting, B. Fonck, P. Piettre (eds.), 1914 : neutralités, neutralismes en question. Bern: Peter Lang, 2017, 271-288.

_______ (ed). Women Writing Poetry, Modernism and War. Paris: CBP, 2015, (i-book).

_______. “When Women Write the First Poem: Louise Driscoll and the ‘war poem scandal.’” Miranda 2 (2010), http://miranda.revues.org/1296.

Lindsay, Vachel. “Mark Twain and Joan of Arc,” Poetry (July 2017) 175.

London, Lucy. Female Poets of the First World War. Blackpool: Posh Up North, 2013.

_______. Female Poets of the First World War: Volume 2. Blackpool: Posh Up North, 2016.

Longley, Edna. Poetry in the Wars. Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe, 1986.

Montin, Sarah. “‘I am not concerned with poetry. My subject is war’. Écrire la Première Guerre mondiale : les enjeux du poème face aux circonstances.” Doctoral Thesis, Paris-Sorbonne, 2015.

Polner, Murray and Woods, Thomas E., Jr. (eds). We Who Dared to Say No To War: American Antiwar Writing form 1812 to Now. New York: Basic Books, 2008.

Reilly, Catherine (ed). English Poetry of the First World War: A Bibliography. London: G. Prior, 1978.

_______. Scars Upon My Heart: Women’s Poetry and Verse of the First World War. London, Virago, 1981.

Roberts, David (ed). Minds at War: The Poetry and Experience of the First World War. West Sussex: Saxon, 1996, 2003.

Sherry, Vincent. The Great War and the Language of Modernism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Silkin, Jon. The Penguin Book of First World War Poetry, 3rd edition, London: Penguin, 1996.

Stallworthy, Jon. The Oxford Book of War Poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Thomas, Edward. “War Poetry,” Poetry and Drama 11.8 (December 1914) 341-345.

[1] While no chapters were devoted to women writers, Eleanor Farjeon is mentioned in conjunction with Edward Thomas, and Katherine Tynan’s name appears next to Yeats (both page 59).

[2] First composed for an ERIBIA seminar on Womens’ War Writings, organized by Amy Wells in Caen November 12, 2015, this paper has evolved during a time of social upheaval, from the terrorist attack on Parisian civilians, November 13, 2015, through the stress resulting from the aftermath of the June 2016 British vote for Brexit and the November 2016 US elections. Whereas nuclear warfare seemed highly unlikely in 2014, that is no longer true, so let us continue to remind ourselves that war means death.

[3] Richard Aldington, Laurence Binyon, Edmund Blunden, Rupert Brooke, Wilfrid Gibson, Robert Graves, Julian Grenfell, Ivory Gurney, David Jones, Robert Nichols, Wilfred Owen, Herbert Read, Isaac Rosenberg, Siegfried Sassoon, Charles Sorley, Edward Thomas.

[4] http://www.westminster-abbey.org/our-history/people/poets-of-the-first-world-war, last consulted February 28, 2017.

[5] The poet casualties of 1915 include: Rupert Brooke, Julien Grenfell, Walter Lyon, Stephen Phillips, Charles Sorley. In 1916: Rex Freston, Cyril Morton Horne, Thomas Michael Kettle, Alexander Robertson, John William Streets. In 1917: T.E. Hulme, Ewart Alan Mackintosh, Charles John Beech Masefield, Patrick Shaw Stewart, Edward Thomas, Arthur Robert Ernest Vernède, Graeme West. In 1918: Philip Bainbrigge, Alfred George Bathurst, John McCrae, Wilfred Owen, Claude Quayle Lewis Penrose, Isaac Rosenberg, Henry Lamont Simpson, John Ebenezer Stewart, T.P. Cameron Wilson.

[6] For further discussion of poets on the monument, see J. Kilgore-Caradec “Les poètes face à la guerre de 1914 : quand la neutralité semble impossible,” I. Bockting, B. Fonck, P. Piettre (eds), 1914 : neutralités, neutralismes en question, Bern: Peter Lang, 2017, 271-88.

[7] Sarah Montin during her thesis defense, November 7, 2015, at Paris-Sorbonne quoted from Catherine Reilly’s 1978 bibliography (as cited in her thesis, ‘I am not concerned with poetry. My subject is war’. Écrire la Première Guerre mondiale : les enjeux du poème face aux circonstances, p. 52). Montin’s thesis was published : Contourner l’âbime : les poètes-combattants britanniques à l’épreuve de la Grande Guerre (2018).

[8] There is no denying that we today are affected by our knowledge of wars in progress and of the refugees that are dying as they try to reach Europe. Some of us think about this quite a bit in fact, whether or not our actions reflect the obsession that such thoughts can become.

[9] Yeats’s several war poems “On Being asked for a War Poem” (1915), “An Irish Airman Foresees His Death” (1918), “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory” (1919) and his famous “Easter 1916” (1916) have probably received more attention than all the war poetry of World War I written by women combined.

[10] Several paragraphs in this section have been reworked from J. Kilgore-Caradec, “Les femmes écrivent la guerre,” in N. Beaupré (ed.), Ecrivains en Guerre 14-18: ‘Nous sommes des machines à oublier’, Paris: Gallimard/Historial de la Grande Guerre, 2016.

[11] Exposure to such toxic chemicals was liable to have strong effects on health, including damage to vital organs such as the liver and spleen, anemia, and the reproductive process. A canary girl, Sara Lumb (the name is cleverly chosen, evoking gas in the lungs) is depicted as a romantic interest for Billy Prior in Pat Barker’s Regeneration (1991).

[12] These figures are offered by Spartacus-educational.com, consulted October 31, 2017: http://spartacus-educational.com/Wmunitions.htm. Other statistics mentioned in this paragraph are from various internet sources, and are estimated accurate; further research is adviseable.

[13] Maev Kennedy, “Honour for factory where female workers died in First World War,” Guardian, October 10, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/10/barnbow-national-filling-factory-female-workers-first-world-war, consulted October 31, 2017.

[14] Edward Skinner’s painting For King and Country (1916) notwithstanding. In 2016 the Mikron Theatre Company of Marsden presented a touring show, “Canary Girls” about the munitionettes.

[15] This information is from “Women in the factories,” featured in the digital exhibit, “Industry in Connecticut during World War I,” https://library.ccsu.edu/dighistFall16/exhibits/show/industry-ct-ww1/women-in-the-factories, with David Drury, New Britain Industrial Museum, New Britain Chamber of Commerce, Library of Congress, Wikimedia, and University of North Carolina. Consulted October 31, 2017.

[16] For more on Dickinson’s war poems, see Shira Wolosky’s ground-breaking study, Emily Dickinson: A Voice of War(1984). It should nonetheless be remembered that Richard Eberhart had commented even earlier on the nature of Dickinson’s war poetry, as Alexandre Ferrere noted in his M2 thesis, “Variations Poétiques sur la Mort : la perte de la figure maternelle et la guerre dans la poésie de Richard Eberhart et d’Allen Ginsberg” (Université de Caen, 2017), 81.

[17] Even Gertrude Stein’s poem “Lifting Belly” which was first begun in 1915 alludes to the war in the line “Not about Verdun” (qtd. Featherstone 447).

[18] Nina MacDonald, “Sing a Song of War-Time,” Madeline Ida Bedford, “Munition Wages,” Mary Gabrielle Collins, “Women at Munition Making” all poems found in Reilly and mentioned by Gillis (106-7).

[19] Richard Eberhart described his “long reach” in The Long Reach, New & Uncollected Poems 1948-1984 as “a long reach at meanings, at manifold meanings…” New Directions, 1984, from the back cover of the volume.

Jennifer Kilgore-Caradec is associate professor/MCF at Université Caen Normandie and is a member of LARCA research team at Université Paris Cité.

Hanns Lipps et la chouette Rébecca.

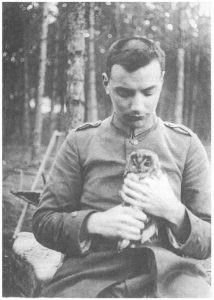

Hanns Lipps et la chouette Rébecca. Soldats allemands en transport vers la France en 1914. Le wagon de marchandises est décoré de slogans légers qui laissent présager une guerre brève.

Soldats allemands en transport vers la France en 1914. Le wagon de marchandises est décoré de slogans légers qui laissent présager une guerre brève.  Edith Stein dans un lazaret en Moravie dans le cadre d’une fête. Edith Stein Archiv Köln.

Edith Stein dans un lazaret en Moravie dans le cadre d’une fête. Edith Stein Archiv Köln.