JENNIFER KILGORE-CARADEC

Keywords

World War I, Wilfred Owen, World War I Centenary, Memorial Sites, Ors

Review

Credit Maxime Turpin

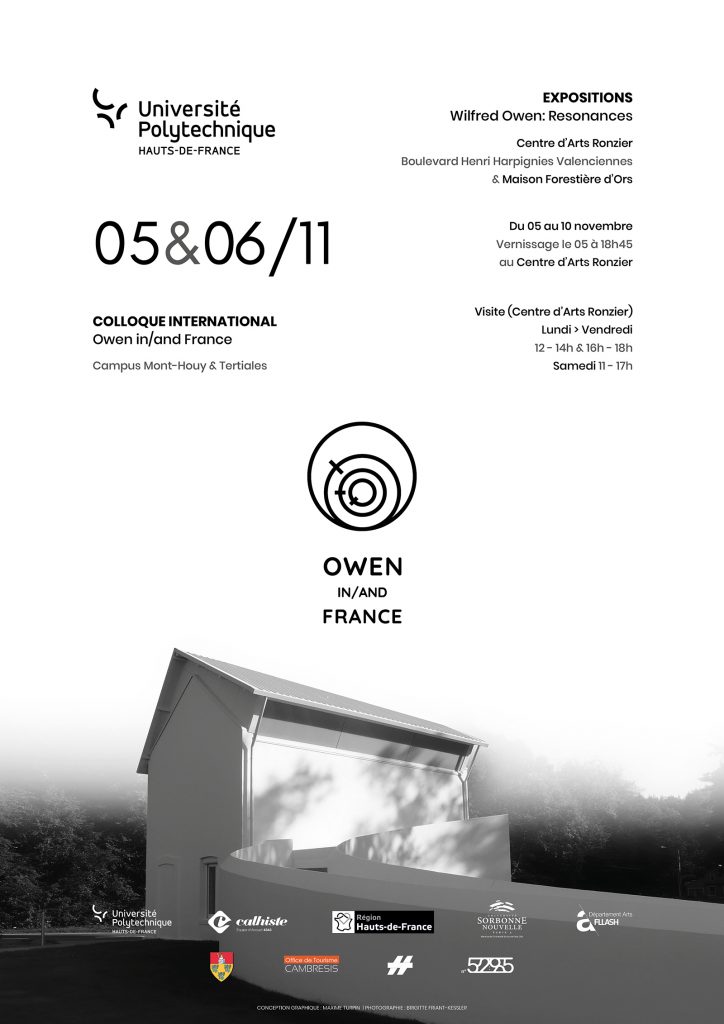

‘Wilfred Owen in/And France’ and Wilfred Owen / Resonances Exhibit (Symposium, November 5-10, 2018 at Mont Huey Campus and at the Forester’s House in Ors, Exhibit November 5-6, 2018, Université Polytechnique Hauts-de-France; organized by Elise Brault-Dreux, Brigitte Friant-Kessler, Nicolas Devigne, and Sarah Montin)

_________________________________

We are presently commemorating the centenary of the Armistice, as no one can ignore after the French government’s inspired ceremony on November 11 immediately followed by the Peace Forum where the world leaders were in attendance, excepting the notable absence of Donald Trump. Further afield from international media coverage, researchers have been grappling with issues of remembrance too. For those who wonder how remembrance can be more than the mere empty shell of a ritual, the art students at University Polytechnique Hauts de France may provide some valuable insights. They prepared artworks about Wilfred Owen’s death, 100 years ago on November 4, 1918, interacting with Owen’s famous poem, ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ under the guidance of Brigitte Friant-Kessler and Nicolas Devigne. Before they began preparing their artworks, on view in the Resonances Exhibit, they visited the Forester’s House in Ors, which is where Owen spent the last evening before he was killed, and they also visited his place of death.

The memorial site was renovated and opened to the public in 2011. A description of the place on the Wilfred Owen Association website insists on the house looking like ‘a solid sculptural object’. Indeed it does from the outside, and resembles a sanctuary on the inside, where draft versions of Owen’s most famous poem, ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ are inscribed on glass panels that cover the walls. Dally Minogue and Andrew Palmer, authors of The Remembered Dead (CUP 2018) described the artful choices made by Simon Patterson in the renovation and design of the Ors Forester’s House memorial during the conference ‘Wilfred Owen in/and France’. They emphasised how the place itself honours Owen’s poetry as much as it honours the poet. Visitors descend a curving white walkway in which Owen’s last letter to his mother, written in this place, is engraved in the walls. A hush goes with them into the cellar where Owen and some 26 other men took shelter, lit a fire, ate dinner, and wrote letters before going to battle in the morning. It is a small space, amounting to less than one square meter per person for sitting, sleeping, and eating. It is no wonder that Owen mentioned the smoke of the fire in a letter that was otherwise euphemistic and reassuring.

The art students of Université Polytechnique Hauts-de-France saw the manuscript of Owen’s poem on the glass surrounding the walls on the ground floor of the house. They took the opportunity to read and understand the text, and they visited the places on the recommended walking tour, including the place of Owen’s death and his grave. This resulted in various artworks, from paintings to collages, films, photographs, and sculptures. ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ was translated into Chinese and juxtaposed with a poem by Chairman Mao on a fan and then photographed. The artworks were often subtle and all transmitted emotion. The transpositions were particularly powerful. They provided a memory that was actualised and in action. An introduction to the exhibit Resonances was given by Nicolas Devigne and Maxime Turpin with Marcel Lubac during the conference.

Why did Owen decide to return to France, after suffering shell shock during the Battle of the Somme, and being treated at Craiglockhart Military Hospital (where he met Siegfried Sassoon and Robert Graves, much as Pat Barker poignantly described in Regenerationin 1991)? As the French specialist of British War Poetry Roland Bouyssou explained during the conference through one of Owen’s letters, Wilfred wrote that he felt like a shepherd to his men. His desire seems to have been to try to help others through the experience of that hell that he knew so well. He was an officer, but from a different background, and had grown up speaking Scouse more than Received Pronunciation, as Paul Elsam pointed out. Elsam recited ‘1914’ with a Scouse accent—demonstrating the point that Owen was a poet from lower classes, as opposed to landed gentry (though he did, before he died, frequent the Sitwells). He considered that school children today should be exposed to Owen’s poetry with the same Scouse accent, since it would make his poetry seem more accessible to a wider audience.

‘Owen in/and France’ was the occasion to remember the role of France in Owen’s life: he started learning French while still young, and prided himself on learning it. He read La Chanson de Roland, Daudet, Verlaine, Flaubert, Renan…and proved to be, at least on one level, just as influenced by French symbolism as T.S. Eliot. While teaching English in Bordeaux (beginning September 1913), one of his students suggested he spend the summer vacation tutoring her child in English. So on July 30, 1914 he arrived at Bagnères de Bigorre. War then broke out, and people looked at him askance, wondering why he had not been drafted. A few weeks later he met a figure that greatly influenced the course of his poetry, Laurent Tailhade, who may be rapidly described as a satirical poet, single handedly playing the satirical role of Charlie Hebdo during his time. Tailhade wrote against anti-dreyfusards in Poèmes aristophanesques(1904). Owen was eventually given the book by the poet, and asked his mother to send him his copy in a letter—and then volunteered to go to war in September 1915. He had been aware of 60-year-old Tailhade volunteering to go to the front in autumn 1914.

Wilfred Owen is the best known British war poet today, thanks to Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, first performed at the consecration of Coventry Cathedral in 1962, and also thanks to Pat Barker. But while Owen is still not a household name in France, there is little excuse for such ignorance, because his poetry has been translated into French by Xavier Hanotte, who also made Owen a fictional character in one of his mystery novels, as Joseph Duhamel noted. Gilles Couderc, specialist of Benjamin Britten and a native of the Pyrenees, spoke of Owen’s possible attraction to Catholicism while at Bagnères de Bigorre where he would have seen Lourdes, if only from the train.

Neil McLennan, a Scottish historian speaking to some forty budding young historians who made a point to be present at the conference, asked everyone to cross their arms, and then attempt to cross them a different way, to concretely demonstrate how difficult it may sometimes be to take new insights about subjects we think we know. He has located the golf course in Edinburgh where Owen, Sassoon and Graves met.

Jérôme Hennebert offered a very intense paper on the French poetics of Owen, moving from English romanticism through French Symbolism and Decadence back into Owen’s war poetry. It was complemented by Laure-Hélène Anthony’s paper about Owen’s last completed poem, ‘Spring Offensive’ and by Michael Copp’s paper showing that Pound as well as Owen drew from the poetry of Laurent Tailhade. Thomas Vuong then offered an analysis of all of Owen’s sonnets to see if the forms were English or French.

Conference participants visited the exhibit Résonances in detail during the inauguration evening, rejoicing in the student’s profound interpretive works. The conference ended the following day with a visit to the Forester’s House in Ors, where we were greeted by the mayor of Ors, who well understands the importance of the place for all poetry lovers. Damian Grant recited two of his poems about Owen, and they were also shared with us in French by Madeleine Descargues. After that, it remained for us to visit the cellar where Owen and and the other soldiers huddled during his last evening alive. Arriving at the ground floor, we all observed the Owen poems projected on the walls in respectful meditative silence.

Jennifer Kilgore-Caradec teaches English at Université Caen Normandie and co-edits Arts of War and Peace with Mark Meigs.