MARGARET GILLESPIE

Abstract

The early years of the twentieth century witnessed the boundaries between masculine and feminine roles in Western society being more keenly contested than ever before, as women encroached further into the public sphere and were increasingly vocal in their demands for political rights and representation. The Great War brought this tension into sharper focus as it paradoxically fostered both a culture of bellicose manliness, while at the same time offering women the possibility of escaping the domestic space and gaining in agency and empowerment. The question of gender and war was also one that engaged and inspired male modernist writers, who frequently « sexed » their aesthetic response to the horror of combat as they posited the compensatory value of art in a time of crisis. Women novelists such as Djuna Barnes and Rebecca West also gave expression to the contemporary struggle over masculine and feminine identity within the context of war but their stance, it will be argued, was somewhat different. Critical of the Great War’s politico-patriarchal imperatives, they also viewed the period as a time and space from which alternative gender configurations might be effectively articulated.

Résumé

Au début du XXe siècle, quand les femmes s’investissent davantage dans la sphère publique et revendiquent plus haut et plus fort leur droit à une représentation politique, les frontières entre les rôles octroyés aux hommes et aux femmes sont plus que jamais contestées. La Grande Guerre fait ressortir cette tension car elle encourage à la fois la culture de la virilité belliqueuse tout en offrant aux femmes la possibilité de s’échapper de la sphère domestique et de gagner en autonomie. Cette interrelation féconde a interpellé et inspiré les écrivains modernistes masculins, qui formulent souvent leur réponse à l’horreur des tranchées en termes sexués, tout en affirmant la valeur compensatoire de l’art en temps de crise.

Le regard des romancières telles que Djuna Barnes et Rebecca West porte également sur la question l’identité masculine et féminine dans le contexte de la guerre, mais leur prise de position est quelque peu différente. Critiques à l’égard des impératifs politico-patriarcaux de la Grande Guerre, elles considèrent cette période comme un espace-temps qui permet l’émergence de nouvelles configurations sociétales et genrées.

Keywords

Djuna Barnes, Nightwood, Rebecca West, The Return of the Solider. T.S. Eliot, T.E. Hulme, Ezra Pound, May Sinclair, Great War, gender.

___________________

The early years of the twentieth century mark a period in Western society where the boundaries between masculine and feminine roles were being more keenly negotiated than ever before, as women moved further into the public spaces of workplace and university and were increasingly present on the political stage (Bockting 21). The Great War brought this tension into sharper focus as it engendered a culture that at once celebrated virile prowess and yet offered many women the possibility of jettisoning the domestic realm as the demands of total war took them to the factory or field ambulance. World War One also lies at the heart of literary modernism, providing impetus and inspiration for modernism’s experimental aesthetic and ideological underpinnings: it is indeed « the great modernist subject » (Goodspeed-Chadwick 17). However it is also one from which female writers have historically been marginalized, just as more broadly speaking, male experience and male writing have long constituted the archetypal modernist text (Felski 10). The following article aims to offer a tentative exploration of the complex interelationship between, modernism, gender and war while also showcasing lesser-known writing on war by women. Starting with male modernists’ twin responses to the horror of the trenches and anxiety over shifting gender paradigms, it will then move on discuss how those paradigms were rearticulated and traditional norms reinstated within a context of war. The article will then turn its attention to the women writers’ reaction to combat: what was their take on the period and how was it received? Lastly in the wake modernism’s recent historical turn and its reevaluation of the current’s female protagonists, it will make a case for the significance of the women writer’s view.

T.S. Eliot’s now famous 1923 apology of Ulysses as “mythic method” established an important critical paradigm for reading the modernist text in the wake of what the poet termed “the immense panorama of futility and anarchy” that was modernity post World War One. In proposing something “stricter” than the conventional realist novel, argued Eliot, the artwork might just counter the hopelessness and chaos of a fallen world and offer “a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving shape and significance” (484, 483)—not just a “heap of broken images”, as the poet famously put it in The Waste Land published the year before before—but a real reconstruction of sorts to “shore” against the “ruins” of civilization (l.22, 430). Of course, Eliot’s comments on Ulysses apply as much to his own work as to Joyce’s: as modernist scholar Alex Goody has noted, the battlefields of the Great War “echo thematically and aurally through The Waste Land” (58). At the same time, this richly intertextual poem offers art as aesthetic compensation for “futility and anarchy” as the “individual talent” of the poet refashions and pays homage to literary “tradition” (Eliot 1921).

This high modernist notion of ordered reconstruction in the face of chaos was often articulated in gendered terms, and not surprisingly so, since “during this period Western society was struggling over where to draw the boundaries between masculine and feminine identity” (Bockting 21). As Margaret Bockting has stressed, the pre-war years saw a significant influx of women into the public sphere:

By the 1910s, greater numbers of women than ever before were attending colleges, earning wages in industries and professions, receiving access to birth control information (and sometimes contraceptive devices) and demanding (and in some states exercising) the right to vote and hold political office. (22)

For modernist theorists such as Eliot, Pound and T.E. Hulme writing around the time of the First World War, the “feminine”—sentimental excess and its aesthetic avatars, decadence and romanticism—, became a leitmotif in their writing on artistic practice as something to be kept at bay. Eliot’s “classicism,”[i] T.E. Hulme’s apology of the “hard and dry” (126), and Pound’s insistence on the importance of writing to be sober and unadorned—“austere, direct, free from emotional slither” (12)—can be viewed as a figurative expression of a broader resistance to female encroachment into the public space[ii]. It finds a “real-life” corollary in the masculinist triumphalism that Theodore Roszak has termed the “compulsive masculinity” of early twentieth-century political rhetoric (92).[iii]

In the face of challenges to conventional gender identities, the early decades of the twentieth century witnessed a reinforcement of the Victorian notion of the separate male (public) and female (private) spheres, with the war in particular offering the opportunity for men to reassert their masculine credentials in active combat. The “ideology of male violence” (Bockting 23) was buttressed by the still popularly held Darwinian belief that man “is more courageous, pugnacious and energetic than woman” (Tylee 124). Militarism was applauded precisely because it encouraged bellicose manliness:

The War emphasized an essential difference between men and women. Women were not combatants […] The war reasserted gender distinctions that women had been contesting: women were frail and had to be defended by strong protectors, who were prepared to kill or die on their behalf. (Tylee 253-254)

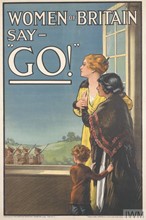

Military propaganda posters of the period on both sides of the Atlantic contributed to constructing the war as a male initiation rite at the same time as they reinforced difference and, crucially, a hierarchy of gender that glorified the man’s role. One 1917 American poster featuring a radiant young woman sporting a male sailor’s uniform bears the caption “GEE!! I WISH I WERE A MAN I’d JOIN THE NAVY BE A MAN AND DO IT UNITED STATES NAVY RECRUITING STATION.” [iv] The implication is not only that maleness is superior and preferable—the envy of women—, but that masculinity is not automatically attributed: rather, it needs to be maintained, earned even, by performing manly deeds (“be a man and do it”).

A second poster[v], this time dating from 1915 and targeting a British audience, also elicits the perceived complicity of the female population to encourage more men to enlist. The poster highlights men’s role as guardians of the weaker sex, as a woman and her offspring look out from within the confines of a clearly delineated domestic space at a regiment of soldiers marching off to war. The mother, the embodiment of passive, helpless British womanhood, enjoins her spouse to go and fight.

Of course, the “gross dichotomizing” (Fussell 75) of this ideological message was only part of the story. Their theoretical formulations notwithstanding, male modernists’ artistic output during and in the immediate follow-up to the Great War often offered a more complex response to the crisis in gender identity. T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”, the title piece in PRUFROCK and Other Observations, (1917) and dedicated to “Jean Verdenal 1889-1915”, a military doctor and a friend of the poet who died in the trenches, portrays a very different form of masculinity to that celebrated in warmongering rhetoric or in Eliot’s writings on poetic practice discussed earlier. As his name suggests, Prufrock displays flaws traditionally associated with femininity: he is prudish, cowardly (“And indeed there will be time/To wonder, ‘Do I dare?’ and, ‘Do I dare’”, l. 38) and feeble (“They will say: ‘But how his arms and legs are thin!’” l. 44), at the same time as being both lured and spurned by indifferent womanhood (“I have seen the mermaids singing each to each/I do not think they will sing to me” l. 124-125). Equally significant is the role accorded the androgynous visionary Tiresias, “old man with wrinkled dugs” (l. 228) in The Waste Land—“the most important personage in the poem” according to Eliot’s notes (n. 218)— and a source of unity rather than anxiety in the work.

However, just as the feminine was beginning to make ambiguous inroads into male modernists’ wartime production, so too were women making advances into the public sphere. Journalism and diaries of the period reveal the extent to which war offered women the possibility of escaping the home and gaining entry in “male centres of power” (Tylee 14), be it in employment in the munitions industry and other previously male-dominated professions, or even across the Channel in France, nursing wounded soldiers or driving ambulances.[vi] In fact, as Tylee notes, so momentous was the experience of female empowerment that “many women who lived through the period saw the War itself as overriding their interest in women’s suffrage.” (14)

In “Hands that War”, an article that appeared in the Daily Chronicle in 1916, journalist and modernist writer Rebecca West stresses the heroic contribution women made to the war effort, describing the harsh and hazardous twelve-hour shifts they endured in munitions factories: “surely never before in modern history can women have lived a life so completely parallel to that of the regular Army,” exclaims West, before enjoining the state to remember “the cold fact that they face more danger every day than any soldier on home defence has seen since the beginning of the war” (Young Rebecca 382).

Yet as scholar Suzanne Raitt has argued, those women who did play an active role in the war effort nevertheless often found themselves faced with the humiliation of their own perceived inferiority: “femininity is repeatedly experienced and represented as shame at times of social and cultural crisis” (66). Modernist May Sinclair’s poetic dedication “To a Field Ambulance in Flanders”, included in A Journal of Impressions in Belgium (1915), the memoirs of the short period she spent there,[vii] speaks eloquently of frustration and regret at not being able to participate more fully in the war, and a sense of women’s own lowly status on the front:

I do not call you comrades,

You,

Who did what I only dreamed.

Though you have taken my dream,

And dressed yourselves in its beauty and its glory,

Your faces are turned aside as you pass by.

I am nothing to you,

For I have done no more than dream (l. 1-8)

The female speaker in Sinclair’s poem portrays herself as “trumped” by the seductive appeal of danger, personified as a bewitching temptress, far more irresistible than a real woman:

Your faces are like the face of her whom you follow,

Danger,

The Beloved who looks backward as she runs, calling to her lovers

The huntress who flies before her quarry, trailing her lure (l. 9-12)

Indeed, the challenge to what Paul Fussell has termed the “simple antithesis” (82) of the official war narrative, a potentially radical moment of promise and opportunity—the risks outlined by West notwithstanding—would prove largely short-lived. As modernist scholar Maren Linett notes, the return to peace saw a backlash against women working: “were they to take jobs from wounded former soldiers? Ought they not to return home and bear children to replace the young men lost in the war, to shore up the nation’s health and pride?” (5).

As regards the construction of the canon of war literature and the literary history of the period, a similar trajectory may be observed, with women’s writing under-researched compared to that of their male counterparts. This is perhaps, as Angela K. Smith suggests, “because women are not obvious participants in the popular mythic representations of the war” (3)—even if the trench experience was one encountered by less than half the total male population and “the roster of major innovative talents who were not involved with the war [as combatants] is long and impressive”, including “Yeats, […] Pound, Lawrence and Joyce […] the masters of the modern movement” (Fussell 313-14).[viii] Thus, as Julie Goodspeed–Chadwick has noted, “canonical collections of war poetry and war writing have historically elided women” (17). Women have been denied space in the traditional literary representations of the Great War because while they lived through it, they did not take part in it directly. Moreover, the New Critical approach, long the dominant “academic discourse” of modernism, laid an emphasis on textual, and by extension cultural, unity, locating modernist artistic triumph in its ability to the transcend the “ruinous vulgarities of modern life” (McDonald, 192), just as Eliot’s essay on Ulysses had argued back in 1922.

Recent re-evaluations of modernism are however increasingly challenging this androcentric “received narrative” (Lamos 2):

What once seemed the exclusive affair of ‘modern masters’, the ‘men of 1914’ (as Wyndham Lewis called them) now stands revealed as a complex of inventive gestures, daring performances, enacted by many who were left out of the account in the early histories of the epoch, histories offered first by the actors themselves and later produced within academic discourse, willingly guided by the precedents of eminent artists. (Levenson 3)

With the historical turn in modernist studies, modernist texts are now being recognized as the site of other forms of reconstruction. The journalistic and fictional writings on World War One by two female modernists, the British writer Rebecca West (1892-1983) and the American Djuna Barnes (1892-1982), not only demonstrate the role of women as critical contemporary commentators on the war, but also show how the ideological “struggle” over the boundaries of male and female roles at play during wartime offered the possibility of new configurations of gender identity, not just the dogged reiteration of well-worn stereotypes. West and Barnes bring the war into the domestic sphere and take the traditionally feminine out onto the battlefield. In laying bare the limits of “compulsory masculinity,” they put forward a bold denunciation of the perversion and inhumanity of warfare, refusing, as West puts it in an article in the liberal American magazine New Republic in 1914, to “scuttle for safety towards militarism and orthodoxy”.

This article entitled “It Is Our Duty to Practice Harsh Criticism” strikes a chord with Eliot’s essay, previously discussed, in its insistence on the redemptive power of creative practice:

Indeed, if we want to save our souls, the mind must lead a more athletic life than it has ever done before, and must more passionately than ever practise and rejoice in art.

But whereas for Eliot, art is posited as a compensation for the horrors of modernity, West’s piece, which she subtitles “a literary manifesto for the ages”, explicitly champions the political role art has to play in wartime in challenging the recourse to comforting old order certitudes—what she acerbically terms the “convention of pleasantness”—when faced with “disgust at the daily deathbed” of the trenches:

Life will be lived as it might be in some white village among English elms; while the boys are drilling on the green we shall look up at the church spire and take it as proven that it is pointing to God with final accuracy.

It is this same quaint rural idyll that West seeks to disturb in her first novel The Return of the Soldier, published in 1918. The text, which takes place almost entirely in the domestic sphere of Baldry Court, an English stately home and is narrated from the viewpoint of Jenny, cousin of the eponymous soldier for whom she harbours unrequited feelings. Recounted through Jenny’s conventional upper middle-class voice, itself positioned on the peripheries of the action, The Return of the Soldier has tended to be read as “woman’s novel”, dealing primarily with emotions and sentiment (Smith 171). Into this ostensibly safe and orthodox frame, however, West brings disruption in various guises. This is by no means the glorious return of the warrior: Chris Baldry, the archetypal soldier of the title, is shell-shocked. Since he is suffering from amnesia, his married life with his “beautiful doll-like” wife Kitty (Smith 172) and his devoted cousin Jenny, the narrator of the novel, has been completely erased from his memory. Instead, he recalls his working-class childhood love, Margaret Allington, the once-beautiful innkeeper’s daughter, now a jaded and dowdy middle-aged woman, whose inferior class status is scornfully and patronizingly underlined by Jenny in the early stages of the novel:

The bones of her cheap stays clicked as she moved […] though she was slender there was something about her of the wholesome endearing heaviness of the draught-ox or the big trusted dog. Yet she was bad enough. She was repulsively furred with neglect and poverty. (25)

In his shell-shocked state, Chris rejects life in the big house—which, as Angela K. Smith convincingly argues, functions as a metonym for the “upper-class Edwardian society” (172)—preferring the “Utopian classless world” embodied by Margaret, and which offers the reader the tantilising vision of what another kind of social structure might possibly look like. This idyll finally comes to a close following a consultation with Gilbert Anderson, a psychiatrist called in by Kitty and Jenny as a “last resort” (Smith 174), who bluntly spells out the reason for the soldier’s amnesia: “‘Quite obviously he has forgotten his life here because he is discontented with it.’” (125) Not surprisingly, it is Chris’s childhood sweetheart —the only woman who truly connects with what Anderson terms his patient’s “‘deep […] essential self,’”— that correctly ascertains how he may successfully be returned to reality: “‘She continued without joy. ‘I know how you could bring him back. A memory so strong that it would recall everything else—in spite of his discontent […] Remind him of the boy.’” (127-128). In an act of heroic selflessness—as curing Chris means relinquishing all claim over his present life—Margaret shows him a jersey and a ball belonging to his infant son, now deceased.

For Kitty, who “suck[s] in her breath with satisfaction,” the end of amnesia signifies an uncomplicated return to the social and gendered status quo “‘He’s cured!’ she whispered slowly. ‘He’s cured!’” (140). However this glib triumphalism is undercut by the narrative voice, which couches Baldry Court, symbol of class privilege and site of an loveless marriage, in menacing, carceral terms: “[an] overarching house […] a hated place to which, against all his hopes, business had forced him to return.” (139). Moreover, being cured not only means being condemned to stifling social conformity and sham connubiality, it also implies being physically and mentally apt enough to return to the war, “that flooded trench in Flanders under that sky more full of flying death than flying clouds, to that No Man’s Land where bullets fall like ran on the rotting faces of the dead…” (140). Chris will be sent back to France a man again—“every inch a soldier” as the narrative voice bitterly claims (140).[ix] However the ambivalence of this “return” to gender certitudes underscores its uneasy status as an ill-fitting role. Chris’s masculinity is expressed oxymoronically: he wears a “dreadful decent smile.” (140) The novel’s dénouement also appears to sound the death knell for the possibility of another form of society, symbolized by Chris and Margaret’s rekindled romance, beyond the strictures of class-ridden Britain. As Wyatt Bonikowski has noted:

The novel is not just about the shock of war but also about the shock of shifting values of gender and class and the overarching power of the state that, especially in a time of war, has an interest in keeping those values rigidly in place. (107)

At the same time however, the voluntarily pat ending suggests “those values”, embodied by Kitty, the least sympathetic and authentic of the novel’s characters (“the falsest thing on earth” according to the narrative voice [136]) have also been irrevocably undermined. In so doing West empties the marriage plot—backbone of the nineteenth-century feminine ideology—, of all its remaining éclat and legitimacy. She also grants narrative and diegetic agency to traditionally marginalized female figures —the spinster and the working-class woman. Indeed, the novel is arguably just as much Jenny’s story as Chris’s as it charts, à la Bildungsroman, her gradual shedding of class prejudice as she learns to appreciate Margaret’s worth beneath the “repulsiv[e]” veneer of “neglect and poverty.” It is a trajectory of self-discovery that concludes in the sexually ambiguous recognition of their mutual lost love object: “We kissed, not as women, but as lovers do; I think we each embraced that part of Chris the other had absorbed by her love.” (138). Crucially, morever, it is not the rigid values of the Edwardian era nor the “mythic method” of Antiquity that offer solace through structure but the character and narrative role of Margaret, the working-class dowd: “at her touch her lives had at last fallen into a pattern; she was the sober thread whose interweaving with our scattered magnificences had somehow achieved the design that other wise would not appear.” (109)

Djuna Barnes similarly sought inspiration from the societal margins in her novelistic exploration of war. Unlike The Return of the Soldier which views the war from the Home Front, Barnes’s novel Nightwood (1936) takes its narrative into the trenches where hegemonic representations of Great War masculinity are satirized through the wartime recollections of one of the text’s characters, the cross-dressing Matthew O’Connor, a central narrative presence in the text who is commonly viewed by critics as its “Tiresias figure” (Madden 178). In one particular vignette, partially excised by publisher T.S. Eliot in the original edition, O’Connor tells the story of a fellow soldier, the “girlish boy” MacClusky (95), whose improbable performance of masculinity earns him a croix de guerre.[x] It is because he panics or goes “all of a fluff”—a term which suggests conjointly femininity, animality and triviality—that he causes the Germans to flee, as they believe a man who uses a gun the wrong way round must be mad:

He’d been standing in the middle of a bridge trying to think where the war was coming from when a douse of Germans loomed up, trying to make the bridge before MacClusky found out, and there he was, the poor frail, gone wild in the centre of the pontoon, and instead of shooting—and why should he know one end of a gun from another—he just went all of a fluff, if you can call murder fluff and swung the heft around and began banging their heads off, and they flew like crazy because even a war has certain calculable reactions processes and this wasn’t one of them, so off they flew, seeing what they though was a wild man in their midst who had no respect whatsoever for the correct forms of slaughter. So he held the fort, as it were, swinging away with the butt of the thing. (276)

As Margaret Bockting has argued, this “atypical combat story parodies both the concept of ‘true’ manliness as well as the idea that war cultivates a healthy masculinity” (34). A figure who, like O’Connor, collapses the gender tensions between active male and female passive roles, MacClusky neither converts to heterosexuality nor knowingly shoots at anyone. In fact MacClusky’s initiation into belligerent manhood (figured here by a slang term for the onset of puberty—balls dropping) brings him not pride and glory, but “misery and horror”: “And [the butt] got about, and all of us grinning because we knew it was the moment his balls fell out with misery and horror that he got the idea” (277). Significantly, it is precisely during the ceremony where MacClusky is awarded the military cross by a general —the juncture that in a more conventional war narrative would form the apotheosis of valour— that the narrative descends bathetically into camp excess. So shocked is MacClusky by the sharp pinprick of the cross on his chest that he recoils in horror and bursts into floods of tears:

He had forgotten what where he was standing and what he was waiting for, when down on his breast flew the croix de guerre with a pin in its tail and at that he gave a jump back that carried him a foot out of line, and […] tears spurted out of him right forward like a lemon. I’ve never seen any tears like those before in my life, though it is the way a boy cries who’s been queer all his hour. (277)

An episode where perversity, obscenity and absurdity happily co-exist, it figures the perversity, obscenity and absurdity of war itself.

This article has argued for the importance of taking gender into consideration when examining the interrelationship of modernism and war. Long side-lined by both high modernism and its academic legacy, and the canon of Great War literature, there has been a renewed critical interest in female modernist war writers in recent years, concurrent with the historical turn in modernist studies and the shift away from more exclusively aesthetic readings. Women writers such as Rebecca West and Djuna Barnes offer an alternative to the critical paradigm that typically saw modernist texts as offering a compensatory artistic reconstruction in the face of a chaotic world. In a deconstructive stance that engages critically with wartime ideological construction of gender, their writings give expression to the struggle over masculine and feminine identity of the period and suggest the possibility of alternative gender configurations, and more broadly, a challenge to the predominant social and class values of their day, suggesting the possibilty of the emergence of a truly modern world.

Notes

[i] Eliot’s 1916 lecture notes on French Literature which can be read as an early articulation of his own literary agenda, championed the value of form and restraint in art—“Classicism”—as opposed to the ‘Romanticism’ of a Rousseau-esque personal and egalitarian impulse. See Potter (218).

[ii] As T.S. Eliot put it trenchantly in correspondence with Pound “I struggle to keep the writing [of The Egoist] in Male hands, as I distrust the Feminine in Literature” (Eliot, 1988, 96). The Letters of T.S. Eliot vol.1, 1898-1922, ed. Valerie Eliot (San Diego, New York, Londres, Harcourt Brace Jovanvitch, 1988), 96.

[iii] For a discussion of gender in the essays and correspondence of Eliot and Pound, and their influence on modernism in the academy, see McDonald. For analysis of Hulme, see Scott (98-99).

[iv] Christy, Howard Chandler (1917), “Gee!! I Wish I Were a Man I’d Join the Navy”, lithograph. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002712088/ accessed 31/05/17. Public domain.

[v] E. V. Kealey. “WOMEN OF BRITAIN SAY – ‘GO!’”, published by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, London. Poster No. 75 Imperial War Museum, http://www.iwm.org.uk Accessed 31/05/17. Public domain.

[vi] the rush of women into engineering and explosives began in the autumn of 1915 and by 1916 there was actually a shortage of female labour in the textile and clothing trades, as women moved into more lucrative munitions work … also increasingly replaced men in private, non-munitions industries like grain milling, sugar refining, brewing, building, surface mining and shipyards” (Braybon 45-46).

[vii] May Sinclair was sent back after only seventeen days.

[viii] I do not mean to suggest that these writers were not affected by the war, any more than the women writing at the time were. Simply, by sheer dint of being men, their status as commentators on the war was perceived as having greater legitimacy. My thanks go to Jennifer Kilgore for her insightful remarks on this point.

[ix] “Go[ing] back to that flooded trench in Flanders under the sky more full of flying death than clouds, to that No Man’s Land where bullets fall like rain on the rotting faces of the dead” (140).

[x] An added irony is that this most improbable tale may actually be based on lived experience that literary critic John Holms recounted to Barnes (226).

Bibliography

Barnes, Djuna. Nightwood. The Original Version and Related Drafts. Edited by Cheryl Plumb. Normal, IL: Dalkey Archive, 1995.

Bockting, Margaret. “The Great War and Modern Gender Consciousness: The Subversive Tactics of Djuna Barnes” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal vol. 30, no. 3, September 1997, pp. 21-38.

Bonikowski, Wyatt. Shell Shock and the Modernist Imagination: The Death Drive in Post-World War I British Fiction. Oxford: Routledge 2013.

Bonnerjee, Samraghni. “ ‘The Lure of War’: British Nurses and their March to the First World War Front”. Unpublished paper.

Braybon, Gail Women Workers in the First World War: The British Experience. Totowa, NJ: Barnes & Noble, 1981.

Cambridge Companion to Modernist Women’s Literature. Edited by Maren Linett. Cambridge, Cambridge UP, 2011.

Eliot, T. S. “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” The Egoist, vol. VI. n°4 September 1919, pp. 54-55; vol VI n° 5, December 1919, pp. 71-72.

– – -.“Ulysses Order and Myth.” The Dial, November 1923, pp. 480-484.

– – -. Selected Poems. London: Faber & Faber, 1954.

– – -. The Letters of T.S. Eliot vol.1, 1898-1922, edited by Valerie Eliot. San Diego, New York, London: Harcourt Brace Jovanvitch, 1988.

Fussell, Paul. The Great War and Modern Memory. Oxford, Oxford UP, 1977.

Goodspeed–Chadwick, Julie. Modernist Women Writers and War: Trauma and the Female Body in Djuna Barnes, H.D., and Gertrude Stein. Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press, 2011.

Goody, Alex. Modernist Articulations: A Cultural Study of Djuna Barnes, Mina Loy and Gertrude Stein. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Hulme T.E. “Romanticism and Classicism” (c.1912), in Speculations: Essays on Humanism and the Philosophy of Art, edited by Herbert Read, New York: Harcourt & Brace, 1924, pp. 113-40.

McDonald Gail. Learning to be Modern, Pound, Eliot and the American University, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993.

Lamos, Coleen. Deviant Modernism, Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1998.

Levenson, Michael (ed. & introd.), Cambridge Companion to Modernism, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2011.

Madden, Ed. Tiresian Poetics: Modernism, Sexuality, Voice, 1888-2001. Madison, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson U Press, 2008.

Pound, Ezra. Literary Essays. London: Faber & Faber, 1954.

Potter Rachel. Modernism and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006

Raitt, Suzanne. “‘Contagious Ecstasy’: May Sinclair’s War Journals,” in Women’s Fiction and the Great War, ed. Suzanne Raitt and Trudi Tate (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Roszak, Theodore. “The Hard and the Soft.” Masculine/ Feminine Readings in Sexual Mythology and the Liberation of Women. Edited by Betty and Theodore Roszak. New York: Harper, 1969, pp. 87-104.

Scott, Bonnie Kime. The Women of 1928. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana U Press, 1995.

Sinclair, May A Journal of Impressions in Belgium. New York: Macmillan, 1915.

– – -. “Dedication (To a Field Ambulance in Flanders”, March 8th 1915, in 19-20 in Tim Kendall, Poetry of the First World War. An Anthology. Oxford, OUP, 2013.

Smith, Angela K. The Second Battlefield: Women, Modernism & the First World War, Manchester & NY: Manchester UP, 2000.

Tylee, Claire M. The Great War and Women’s Consciousness. Basingstoke: The Macmillan Press Ltd, 1990.

West, Rebecca. “It Is Our Duty to Practice Harsh Criticism. A Literary Manifesto for the Ages.” New Republic, November 7, 1914. https://newrepublic.com/article/71896/duty-harsh-criticism Accessed 04/02/18.

– – -. The Young Rebecca: Writings of Rebecca West 1911-17 edited by Jane Marcus. New York: Viking, 1982.

– – -. The Return of the Soldier (1918). London: Virago, 2010.

Margaret Gillespie is an English lecturer at the Université de Franche-Comté, where, with Nella Arambasin, she coordinates, the Normes et créativités axis of the Centre de Recherches Interculturelles and Transdisciplinaires (ea3224). Author of a PhD on Djuna Barnes, she has published broadly on modernism and gender and has also co-edited several volumes in the fields of gender and cultural studies.

Une réflexion sur « Gender and war: modernist reconfigurations in Rebecca West’s The Return of the Soldier (1918) and Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood (1936) »

Les commentaires sont fermés.