MEGAN ROBERTSON

Keywords

Collective Memory, Mediation, World War I, Canada, Popular Culture, War Poetry, John McCrae, “In Flanders Fields” (1915), Rudyard Kipling, “Recessional” (1897), War and Sports, Montreal Canadiens, Commemorations,

Abstract

“In Flanders Fields” by John McCrae is an oft-repeated poem at Canadian Remembrance Day services. This paper examines how lines from the poem are used in two instances that the poet might never have imagined – on the reverse of the Canadian ten-dollar bill and as a motivational slogan in the dressing room of a professional hockey team. Drawing on James Wertsch’s analysis of collective memory made possible through textual resources, this paper discusses how the poem has come to function as a type of transparent frame for promoting particular collective sentiments. The poem itself becomes an object to draw attention to contemporary sentiments of mundane nationalism (in the case of the ten dollar bill) and a celebrated athletic heritage (in the case of the hockey dressing room). In each case the specific events of the Great War are obscured by the manner in which the mediated text brings McCrae’s words close to particular communities without referring back to the conflict itself.

____________________

In 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae composed a piece of poetry that has had an enduring presence in the Canadian imagination. McCrae – a veteran of the Boer War and a respected physician and academic – penned “In Flanders Fields” following the battlefield death of a close friend and former student, Alexis Helmer. Since its origins in May 1915, the poem in three stanzas has become a standard part of Canadian remembrance services on November 11. Children regularly repeat the poem in school assemblies. The familiar poppies and the bravely singing lark that close the first stanza are used by educators to guide literary and artistic projects leading up to Remembrance Day. While nearly a century has passed since the Great War began, its impact on Canada cannot be understated. However, the memorialization of the conflict, as Jonathan Vance points out – that it was a moment of great national unity between Anglophone and Francophone publics and that those who served participated in a willing (predominantly Protestant) Christian sacrifice, has much to do with a post-war desire to make sense not only of the loss of over 60,000 men, but to foster particular social, cultural, and religious values as integral parts of Canadian identity in the early twentieth century. In an era of change wrought by war and sweeping economic and political upheavals, McCrae’s poem served as a reminder of the continuity between those who had served, who had paid the ultimate sacrifice, and those who remained to carry on the torch in future battles.

“In Flanders Fields” is indeed part of a set of national commemorative practices surrounding Remembrance Day, however, it also appears in unexpected places. The permutations, interpretations, and appropriations of McCrae’s literary text have led us a long way from the Western Front of the Great War. In fact, they lead to two very different sites – the reverse of the Canadian ten-dollar bill and the dressing room of a professional sports team, the Montreal Canadiens. By discussing these two examples, I hope to show that the poem itself acts as a type of embedded transparency that is persistently present but is rarely a consciously considered aspect of Canadian collective memory. In these instances, particular lines from “In Flanders Fields” are lifted from their place in the poem and recast as tools for something else. James Wertsch describes this reworking of a text in Voices of Collective Remembrance. He writes that

[w]ithout our being fully aware of it, the cultural tools we employ to remember something like … World War I have a sort of memory, or at least memory potential, built into them. Furthermore, these cultural tools and the affordances and constraints built into them are unequally distributed among various collectives, and as a result these collectives may by expected to remember the “same” event differently. (54)

Critically exploring the unequal distribution of the memory potential in “In Flanders Fields” as it is selectively used on the Canadian ten-dollar bill and in the Canadiens’ dressing room, raises larger questions about collective memory and collective belonging. Who are the dead of Flanders speaking to in the twenty-first century? Who today carries the torch passed so many years ago and what form does the contemporary battle take? While these are metaphoric questions of battles and torches, they illuminate how present-day efforts at Great War remembrance often tell us more about contemporary concerns surrounding active and latent forms of remembering associated with different types of communities, rather than the actualities of the 1914-1918 conflict.

Text and Context

When he wrote the poem in 1915, John McCrae was in his early forties – a bachelor, though a sought after dinner guest in Anglophone Montreal before enlisting in the Canadian Expeditionary Force – and well established in the Canadian medical field as a respected pathologist and educator for his work at McGill University (Graves). As a poet, McCrae’s verse was published in university periodicals through the late nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries. His death from pneumonia in January 1918 while serving in Belgium meant that he never learned of the enduring resonance and popularity of his poem, first published without attribution in Punch in 1915 (Prescott). McCrae himself is an unlikely hero-figure. Jonathan Vance describes an oft-used photograph of McCrae as follows: “his uniform fits poorly over too-sloping shoulders, his hair hangs in an undignified thatch, and his mouth has a strange lopsided quality” (199). With his passing, McCrae joins the dead of his poem – fixed forever in the fields of Flanders while those who survived and those who would come later are left to heed the exhortations of the fallen. Nearly a century after the Great War, Vance notes: “modern critics may be lukewarm to the poem, but contemporaries could scarcely find a superlative sufficient to describe it” (199). Despite its popularity as an integral aspect of Remembrance Day services across Canada, it is rarely studied as a piece of literature. Critically evaluating the poem requires moving beyond rote repetition and asking difficult questions about conflict, propaganda, and remembering.

In her 2005 paper on McCrae’s poem entitled, ‘“In Flanders Fields » – Canada’s official poem, breaking faith,’Nancy Holmes offered a literary analysis of the sonnet. Holmes’ work responds to Paul Fussell’s condemnation of the poem in The Great War and Modern Memory where Fussell derides “In Flanders Fields” as propaganda and worthy only of scorn. Indeed, the poem can expose what Holmes describes as “all sorts of feelings of discomfort we have about colonialism, imperialism, warmongering, homophobia, and falseness”, but she acknowledges that there is a beauty and a power to it that contemporary critics may miss if they are quick to revile McCrae as a jingoist empire-endorsing proponent of war (25). The truth of the matter is complex and is reflected in contemporary feelings for the poem, which can best be described as an unusual blend of embarrassment and pride. These contemporary feelings also mirror the conflicted public sentiment for Canada’s recent military involvement in Afghanistan where critics view the mission as a betrayal of Canadian values beyond the scope of the imagined role of Canada as an international peacekeeper while supporters of service men and women, at the time of this writing, mark the return of those killed in action with somber observances on one of the nation’s busiest highways. “In Flanders Fields” does act as reminder of Canada’s complex past, but before I turn to two of the poem’s current (mis)appropriations, it will be helpful to take a closer look at the text itself:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up the quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

The three stanzas of rhyming verse here are not in any sense a literary innovation. The poem succeeds as a cultural tool in part because of its structure, which lends itself to recitation and repetition. But what exactly is being communicated in McCrae’s poem? “In Flanders Fields” features a speaker who advocates for the fallen soldiers as one of the dead. The kinship implied in the third line is stated clearly in the first line of the second stanza: “We are the Dead”. When the poem was written in 1915, the worst fighting of the First World War was still to come. The promise of adventure that might have attracted Canadians to enlist in the war effort was replaced with the growing realization that the Great War could go on for years as a battle of attrition. The speaker of “In Flanders Fields” urges his addressee to continue the fight as a way of “keep[ing] faith” with those who have already paid with their lives. The poem is a pact between the living and the dead and it has very little to say about the events of the battlefield. Here, McCrae’s poem differs from the work of two well-known British War poets. Rupert Brooke’s “The Soldier”, written by a man who would never make it to battlefield, glorifies even the opportunity that an English soldier might have to die for his country. At the other end of the spectrum, Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est” questions the notion that any glory could be found in horror of the War. With “In Flanders Fields” there are no graphic depictions of life and death in the trenches, nor is there any mention of King, Empire, or country. For these reasons, the lack of battlefield specificity and the emphasis on the relationship between the speaker and the addressee – “you” – lends the poem to reconfigurations where the original context of the piece can be obscured.

Cultural tools and Communities

Jonathan Vance begins a chapter of his seminal work on the mythology of the Great War in Canada, Death so Noble, with a discussion of “In Flanders Fields.” He cites a 1930 newspaper editor who comments that the poem “passed into our common language, its thought was embedded in the thought of the generation for whom it was written; it has remained a heritage for the indefinite future” (199). In this example, “In Flanders Fields” is clearly more than a poem, it is defined as part of a Canadian common language, embedded in national thought, and part of a heritage to be passed on to future generations – this is the very definition of a textual resource as cultural tool. James Wertsch uses this term – “textual resource’ – to describe how a created narrative stands in or mediates between an event and our understanding of that event. Here the event in question is Canada’s participation in the First World War and our twenty-first century understanding of the conflict. Wertsch goes on to suggest that using textual resources is perhaps “not really a form of memory at all, but instead a type of knowledge – namely, knowledge of texts” (27). If collective understanding of something like the First World War is based on a text that stands between our present and our past, a poem like “In Flanders Fields” becomes a lens through which we can view past events in Canadian history. However, if there is no common understanding that links “In Flanders Fields” specifically to the First World War, the poem can be appropriated to serve a variety of needs. McCrae’s poem might have been common language for Canadians in the interwar period as Vance notes, but in its present uses, on the ten dollar bill and in the Montreal Canadiens’ dressing room, the lines of “In Flanders Fields” are only tangentially related to the 1914-1918 conflict.

In his discussion of the memory potential embedded in cultural tools, Wertsch draws a distinction between implicit and imagined communities. Implicit communities are made up of people “who use a common set of cultural tools even though they may be unaware of this fact and may make no effort to create or reproduce their collectivity” (64). These implicit communities differ from the “imagined communities” that Benedict Anderson details in his 1983 work where individuals share a sense of community by sharing a form of media like a newspaper, a particular edition of a book, and in the more contemporary sense, viewing the same television program and web pages. Both Anderson and Wertsch explore the peculiarities of nationalism – how diverse peoples form allegiances within geographic and socio-political borders – but for Wertsch, the suggestion of an implicit community allows for the fact that people use cultural tools for their individual purposes without concern for the fact that those tools circulate amongst a wider public. Individuals in implicit communities use cultural tools as utilities; once the tools have served their purpose, they are rarely given attention. For imagined communities, cultural tools offer links to other people both past and present. In the two instances I discuss below, McCrae’s words become free floating mythological signifiers that drift further and further from the signified (Barthes) – the Allied dead of the Western Front. However, as cultural tools, the use of “In Flanders Fields” on the ten dollar bill and in a hockey arena have in common that both are associated to two very different communities: an implicit one which pays little mind to McCrae’s poem and an imagined one with a specific cultural heritage that has a very limited relationship to the Great War.

Paying the Price: (in)visible memory potential

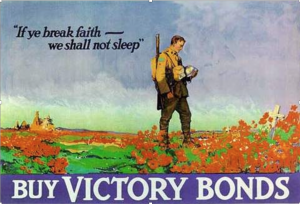

One of the poem’s first commercial uses was in a 1917 promotion for Canadian victory bonds (see figure 1). Here, a soldier stands amidst poppies gazing reverently at a grave behind a ruined village.

Fig. 1. Victory Loans Campaign Poster, 1918; If Ye Break Faith…; CWM 19850475-013; Canada and the First World War; Canadian War Museum; Web; 18 November 2011. © Canadian War Museum.

The audience for this advertisement is assumed to be familiar with McCrae’s poem so that the line that appears in the top left-hand corner without attribution to the author or even the poem from which it is drawn. The Victory Bonds advertisement shifts the notion of a contract – an obligation still exists, but it is no longer between the dead speaker and living combatants. The contract here is one of financial support from the home front population of Canada to soldiers in Europe. By selectively using lines from the poem we can gloss over the more troubling bits where the speaker asserts himself as a representative of the fallen with the words “We are the Dead”. As they are configured in the Victory Bonds image, the men who lie in European graves are sleeping, at peace, and will continue to rest soundly so long as the living fulfill their side of this financial bargain.

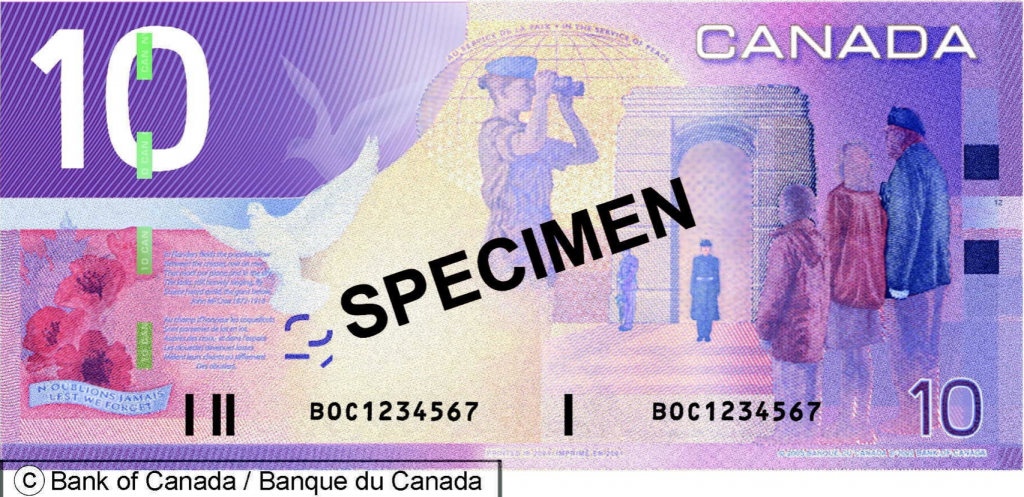

Ninety years after the Victory Bonds campaign made use of McCrae’s words, a connection between money and “In Flanders Fields” continues with the “Canadian Journey” edition of the ten-dollar bill first released in 2001 (see figure 2), which features the first stanza of McCrae’s poem in English and in French, Canada’s official languages (all bills in this series include quotations or verse in both languages). Once again, McCrae’s poem is a textual resource being exploited for a particular purpose.

However, when using a ten-dollar bill one tends not to actively remember much about the bill itself. Like any form of currency, the ten-dollar bill is by definition a cultural tool, considering that we live a society where we have agreed to exchange bits of coloured paper and metal discs for goods and services. Both the monetary and textual resources require what Wertsch terms an “active agent” – an individual who purposely engages with the material. In the case of the ten-dollar bill, the monetary use trumps the memory potential of the textual resource “In Flanders Fields.”

If we are to be active agents, moving beyond the role of individual actors in an implicit community and actually engaging with the words and symbols depicted on the ten-dollar bill, it requires a concerted effort. Actually reading the first stanza of “In Flanders Fields” is difficult – the purple script in tiny font on a pink background can be easily overlooked. The memory potential here goes largely unexploited – unless we know why Flanders is important, unless we have heard and repeated the poem on an annual basis, there is no context for remembering here. We don’t actually need to know about the specifics of the First World War at all if we are already familiar with the poem as part of an established pattern of remembrance. By including the first stanza, no individual is singled out – “you” – are not called upon to carry the torch, but to think about how “In Flanders Fields” works in combination with the other symbols depicted on the bill.

Clustered together with the first stanza of the poem at lower left is a collection of poppies and a banner that reads “lest we forget: n’oublions jamais”: a symbol and a slogan associated with the First World War but without clear attribution to Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “Recessional”, from which it is drawn. While McCrae is identified as poet here, the explicit reference to the dead of the battlefield is missing. In fact, Canadians seem to have little to do with battlefields judging from the collection of images on the bill: a dove hovers near McCrae’s words, while a female soldier uses binoculars to gaze into the future underneath the phrase “in the service of peace”. Finally, on the right, a representative trio gathers at a monument where two members of the military stand watch. There is no war here. Not only do we skip over the overt reference to the dead in the truncated version of the poem, the third stanza about “taking up the quarrel with the foe” is also missing. Despite Canada’s participation in three major conflicts in the twentieth century and the nation’s current involvement in Afghanistan, the Canadian imagination is largely committed to thinking of our military as peacekeepers working only, as the text at the top of bill reads, “in the service of peace” (Jefferess). Wertsch cautions us that textual resources, like the symbols displayed here, “are not neutral cognitive instruments that simply assist us in our efforts to remember. Instead we are often committed to believing or not believing them, sometimes in deeply emotional ways having to do with fundamental issues of identity” (9). By selectively using “In Flanders Fields,” the bill gestures towards a sanitized version of Canada’s past military involvement.

Collective Memory and the Canadiens

When the first stanza of “In Flanders Fields” becomes one of many “cultural tools” to think about war and remembrance, it loses its specific reference to the First World War. Wertsch’s notion of ‘distributed collective memory’ explains why personal understandings of the 1914 to 1918 conflict vary so widely. There is no one collective consciousness that mediates a community’s understanding of the past. Instead, memories are heterogeneously distributed amongst the members of the community and while individuals may share similar memories, they will also have participated in the same event in similar ways (Wertsch, 25). My own feelings towards the poem are mixed – it is impossible for me to “un-know” or stop remembering the Great War when I read “In Flanders Fields”, but I find myself getting caught up in the nostalgia and mythology that surrounds the poem – am I really remembering the events of the Great War when my mind wanders to primary school assemblies or televised Remembrance Day ceremonies? For some reason I am more comfortable with a professional sports team’s obvious appropriation of McCrae’s poem than the easily missed first stanza on the ten- dollar bill. The unabashed co-option of the poem by a general manager with a love of poetry (“Habs greatest GMs inducted into Builder’s Row”) who reached the rank of Lance Corporal in the Great War seems more appropriate than a bureaucratic committee determining which symbols appropriately represent the nation with its Anglophone and Francophone tensions. While Frank Selke’s military service is glossed over in biographies and historical accounts of the Canadiens, the Hockey Hall of Fame notes that he began his sports administration career at the age of 14 and would coach a University of Toronto team to the Memorial Cup in 1919 (“The Legends”). At the outbreak of the Second World War, Selke remained in Canada, heading the Toronto Maple Leafs organization on behalf of another legendary hockey executive — Conn Smythe — who raised an artillery battalion to serve overseas. Managerial decisions made during the war would lead to a falling out between the two that would prompt Selke’s move to the Canadiens in 1946.

“[T]o you from failing hands we throw the torch / be yours to hold it high », the two lines in the Montreal Canadiens dressing room are a textual resource for the players, the organization, and the collective Canadiens fan base. The quotation links the past of the most successful hockey organization in the world, founded in 1909, to the current version of the team (fig. 3). At first it seems odd to find an English Canadian war poem in the largest city of a province that basically had conscription forced upon it in with the Military Service Act of 1917 (Hodgins, Rutherdale). The decision to install the words in the dressing room was Selke’s. The Anglophone from Kitchener, Ontario (which was known as Berlin until the outbreak of the Great War), chose to have the phrase painted — in English and French — above the lockers of the players who would become some of the most legendary men to ever play the game. As Selke set about building one of the greatest teams in Montreal Canadiens history (as general manager of the franchise from 1946-1964, he helped to assemble a team that would win Stanley Cups in seven years), he actively sought to promote Quebec-born Francophone stars while “downplay[ing] the huge contribution of the primarily al-English front office” (Goyens and Turowetz, 91-2).

At the centre of this dynasty was Maurice Richard, a man Douglas Hunter calls “a symbol of the French-Canadian race, a mythic figure for the people of [Quebec]” (147). Richard was the first player to score fifty goals in fifty games, he won eight Stanley cups, and is memorialized in a trophy honouring the league’s annual scoring leader. The famous number nine is immortalized in children’s books, poetry, art, and film. He embodies the cultural, linguistic, and sporting hopes of an entire cultural community. There is no comparative figure in Anglo-Canadian history.

Richard’s notorious glare gazes out at the current roster of Canadiens from below the lines of “In Flanders Fields.” Here it is very clear from whom the torch is being thrown. Players face these words and the portraits of past Canadiens legends before every home game. Visitors to the Bell Centre have the opportunity to tour the dressing room when it is not in use by the players. Tourists can imagine themselves as part of the team. Even for those who do not have the opportunity to attend games in Montreal, the shared experience of watching Saturday evening games has helped to foster a nation-wide imagined community. In Canadiens Legends Montreal Hockey Heroes, Mike Leonetti writes: “even on television the Forum [the Canadiens’ arena from 1926 to 1996] had a special air about it. With the seats close together, there was little room to maneuver, but it was a magical place, especially when the Canadiens were on top of their game” (14). In some ways, the Forum is much more real than the fields of Flanders that MacCrae writes about. The ghosts of the Forum – those who helped the club to twenty four Stanley Cups – seem to loom as large, if not larger than the thousands of young Canadians who rest in fields in Western Europe. As legendary hockey players succumb to age and illness, their names, numbers – and at times their mortal remains, (Richard lay in state at the Bell Centre following his death in May 2000) – are honoured.

Yet, those who fell in the Great War were never repatriated to Canada. Remembering the Canadian war dead has always required an imaginative investment in connecting the there and then of early twentieth century Europe with the here and now of contemporary Canada. It is as if Canadians have learned to remember the Great War via proxy and as the event itself recedes fully out of living memory, the tools used to mediate that remembrance can become unnervingly flexible in that they can be co-opted to serve the needs of present-day communities whose connection to the conflict is increasingly tangential.

Holding High the Torch: Contemporary Reflections

The key difference between the two uses of “In Flanders Fields” – on the ten-dollar bill and in the Montreal Canadiens dressing room – is the existence of two communities that Wertsch identifies: the imagined community and the implicit community. The first stanza of “In Flanders Fields” on the ten-dollar bill is a textual resource for an imagined community, transitioning out of its function as a resource for an implicit community when an individual pauses to reflect on the minute print. In a hockey arena in Montreal, McCrae’s words serve as the guiding link between past glories and present and future hopes for athletic success. For players in the dressing room, the words likely become part of the décor over time, fading from everyday awareness until one pauses again to consider the lines that were composed nearly a century ago. Regardless of how “In Flanders Fields” is used as textual resource, Wertsch reminds us that “Collective remembering is (1) an active process, (2) inherently social and mediated by textual resources and their affiliated voices, and (3) inherently dynamic. However we go about building on these claims, the voices of collective remembering promise to shape memory and identity for as long as we can peer into the future” (178). Key to this reflection on collective remembering is the fact that individuals themselves determine how they use textually mediated memory resources for their own specific purposes. Wertsch notes that “despite all [of the theorizing and analysis] we can’t ever say what people do with a text or if the recipient does what the producer intended” (117). John McCrae never had the opportunity to comment on the adoption of his poem as a national symbol or a cultural tool, of remembrance. However, the speaker in his poem directly addresses the reader; it is up to the reader to decide if the torch, and the complexities of nationalism, sacrifice, and the glorification of the noble dead are worth contemporary reflection and imagination.

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verson, 1991.

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers Trans. New York: Hill and Wang, 1972.

Brooke, Rupert. “The Soldier.” The Wordsworth Book of First World War Poetry. Ed. Marcus Clapham. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Ltd., 1998. 18.

“Canadian Ten Dollar Bill.” Canadian Journey. 2001. Bank of Canada, Ottawa. jpeg.

Fussell, Paul. The Great War and Modern Memory. New York: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Goyens, Chris and Allan Turowetz. Lions in Winter. Scarborough: Prentice-Hall Canada, 1986.

Graves, Dianne. A Crown of Life: The World of John McCrae. Staplehurst: Spellmount, 1997.

“Habs greatest GMs inducted into Builder’s Row.” Canadiens.com, The Official Site of the 24-Time Stanley Cup Champions. 11 January 2007. Web. 21 November 2011.

Hodgins, Bruce, W. Canadiens, Canadian and Québécois. Toronto: Prentice-Hall of Canada, 1974.

Holmes, Nancy. “‘In Flanders Fields’ – Canada’s official poem: breaking faith.” Studies in Canadian Literature 30.1 (2005): 11-33.

Hunter, Douglas. War games: Conn Smythe and hockey’s fighting men. Toronto: Viking, 1996.

If Ye Break Faith. 1917. CWM 19850475-013. Canadian War Musem, Ottawa. War Museum. Web. 18 November 2011.

Jefferess, David. “Responsibility, Nostalgia, and the Mythology of Canada as a Peacekeeper.” University of Toronto Quarterly. 78.2 (2009): 709-727.

Kipling, Rudyard. “Recessional.” Kipling Poems. Ed. Peter Washington. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007. 95-96.

Leonetti, Mike. Canadiens Legends: Montreal’s Hockey Heroes. Vancouver: Raincoast Books, 2003.

Owen, Wilfred. “Dulce et Decorum Est.” The Norton Anthology of Modern and Contemporary Poetry. Eds. Jahan Ramazani, Richard Ellmann, and Robert O’Clair. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2003. 527-528.

McCrae, John. “In Flanders Fields.” In Flanders Fields and Other Poems. Toronto: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1919. 15.

Prescott, John F. In Flanders Fields: The Story of John McCrae. Boston: Mills Press, 1985.

Robertson, Ian. “To you…” 2010. jpeg.

Rutherdale, Robert. Hometown Horizons: Local Responses to Canada’s Great War. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2004.

“The Legends.” The Official Site of the Hockey Hall of Fame. Web. 21 November 2011.

Vance, Jonathan. Death So Noble: Memory, Meaning and the First World War. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1997.

Wertsch, James, V. Voices of Collective Remembering. Port Chester: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Megan Robertson completed her PhD, “Networks of Memory: Creativity, Relationships and Representations” in 2017. She is currently working as Learning Strategist at Kwantien Polytechnic University. She has recently published: “What Sound Can Do: Listening with Memory” in BC Studies 197 (Spring 2018) and “Epistolary Memory: First World War Letters to British Columbia” in BC Studies 182: The Great War (Summer 2014).