STEVE DIXON

Abstract

Steve Dixon (Lasalle College University of the Arts) presents a film interpretation of Eliot’s The Waste Land which he completed with his science of the arts students. Dixon examined the “dizzying array” of potentialities that came with translating the poem into a cinematographic. Despite Eliot’s urging against the remediation of his work, Dixon supports transmediality to touch a new, wider, and younger audience, especially since the poem has taken on a “new resonance” in light of the anxiety triggered by the pandemic and the climate crisis. Based on snippets from the film, Dixon details how award-winning composer Joyce Beetuan Koh’s combination of musique concrète and synthesised sounds enabled an amplification of narrative, psychological, and theatrical aspects of the poem. This feeds into Dixon’s broader desire to enlarge the meanings of the poem thanks to the superposition of sounds and visuals, an effect also reflected in the London- and Southeast-Asia-based shooting locations alternatively featured in the film.

Résumé

Steve Dixon (Lasalle College University of the Arts) présente une interprétation filmique de The Waste Land réalisée avec ses étudiants en sciences de l’art. Il étudie « l’éventail vertigineux » des potentialités ouvert par la transposition du poème en images cinématographiques. Malgré l’hostilité d’Eliot envers toute remédiation de son œuvre, Dixon favorise la transmédialité dans la perspective de toucher un public nouveau, plus large et plus jeune, surtout depuis que le poème a acquis « une nouvelle résonance » à la faveur du climat d’anxiété produit par la pandémie du Covid et la crise climatique. À partir d’extraits du film, Dixon montre comment la combinaison de musique concrète et de sons synthétisés du compositeur primé Joyce Beetuan Koh amplifie certains traits narratifs, psychologiques et dramatiques du poème. Cette démarche s’inscrit dans le projet plus large de Dixon de démultiplier le sens du poème grâce à la superposition des sons et des images, un effet également rendu par les lieux de tournage du film situés alternativement à Londres et en Asie du Sud-Est.

——-

Introduction: making choices

I recently directed a film interpretation of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922) in a research collaboration with students and staff at LASALLE, University of the Arts Singapore. Revisiting T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (2021) was shot in London, Singapore and Southeast Asian countries including Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia. All the film is original, without use of any stock or found footage, and mixes documentary-style imagery (from the river Thames to the landscapes and temples of Southeast Asia) with dramatised sequences with actors playing the poem’s characters such as the Hyacinth Girl, Madame Sosostris, Tiresias, the Typist and the ‘young man carbuncular’. Transposing the poem into a film is of course an act of translation, and in a fundamental and profound sense.

Translators of texts are faced with difficult choices – about words and language, sentence structures, flows and emphases. But translating a poem into another medium changes its very ontology and provides altogether different choices … and challenges. Turning The Waste Land into a film proved a complex and daunting, but highly stimulating task. The poem is so full of visual and classical allusions that it presents a film director with a dizzying array of decisions about potential visual imagery and audio effects. It also opens up questions around which narratives to dramatise and make literal by using characters on screen, and which to render more impressionistically or abstractly. [Figure 1] The poem’s fragmented structure and quick-fire vignettes simultaneously guide and challenge the filmmaker to make important audio-visual and narrative choices, as well as editing decisions around pacing, montage strategies, superimpositions and special effects.

Figure 1: ‘And we shall play a game of chess …’ Tiresias (Steve Dixon) and the Woman who ‘drew her long black hair out tight’ (Kristina Pakhomova).

Film versions of Eliot’s poems are a rarity, with the two major examples being adaptations of previous stage performances: actor Fiona Shaw’s acclaimed solo recitation of The Waste Land (1995, directed by Deborah Warner) and the critically ridiculed and commercially disastrous movie version of Andrew-Lloyd Webber’s musical dance-theatre show CATS (2019, directed by Tom Hooper) based on Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. Eliot actively discouraged remediation of the majority of his poems, including even the use of musical accompaniments; and changing the essential nature of a work of art is always controversial. However faithfully or well it is undertaken, the ontological shift from text into film will inevitably raise questions over interpretation, and face criticism as a result. At the core of this is the long-held argument that ‘the film is never as good as the book’ (or in this case the poem), since a reader’s vivid and fluid imagination will always outshine a director’s singular and all too concrete interpretation.

Nonetheless, filmic remediations of classic literary works (for example, by Shakespeare and Austen) have opened them up to new, wider and younger audiences, and this was part of my logic in creating the film within an educational context. The easing of previous copyright restrictions on adapting The Waste Land into new aesthetic forms was announced in 2021 by the Eliot estate and publisher Faber, to celebrate the poem’s 2022 centenary, and led to permission for my film interpretation. It has been screened at a number of film festivals, winning awards including best experimental film, and is now available online:

Published in 1922, the poem arose in the wake of the global trauma of World War I and the personal trauma of Eliot’s mental breakdown in 1921. I would suggest that today it remains as resonant as ever, particularly since we are now also affected by anxiety and trauma, including through a growing climate change crisis and the effects of a devastating global pandemic. Thus, Eliot’s bleak yet beautiful meditations on fear, isolation and alienation take on whole new resonances a hundred years after he penned them.

A Southeast Asian perspective

My Singaporean colleagues and I translated the poem to provide a particularly Southeast Asian take. For example, the film opens with a title sequence set against a high-angle wide shot of the crammed, polluted cityscape of Manila in the Philippines, with a factory fire raging, sending thick plumes of smoke billowing into the sky. [Figure 2] While the poem describes desert landscapes, Eliot makes clear that modern cities are equally types of waste lands, experiencing urban decay, cultural death and spiritual infertility. While largely set in London, the poem frequently travels East, with many allusions to Asian cultures and religions, and the film draws on Southeast Asian cultural ceremonies, as well as Hindu and Buddhist iconography, igniting strong and sometimes surprising connections with the poem’s ideas.

Figure 2: ‘April is the cruellest month …’ The opening image of a smoke-shrouded Manila.

One example counterpoints footage of a Balinese Kecak dance-music performance depicting a story from the Hindu Ramayana with Eliot’s allusions to the rape of Philomel in Greek mythology. The imagery shows the moment of abduction of the goddess Sita, as she tussles with the evil King Ravana, who violently tugs a piece of her clothing as he pulls her offstage, while the Voice Over narrates: ‘The change of Philomel, by the barbarous King / So rudely forced’. The climax of the same Kecak performance is used later, at the end of ‘The Fire Sermon’ section of the poem. A barefoot dancer who is in a trance state, playing the monkey god Hanuman, jumps into a fire and sits within it, before spinning round and kicking burning embers in all directions. For the Balinese, this spectacular sequence is a ritualised exorcism to expel evil spirits, and is juxtaposed with Eliot’s words ‘burning burning burning burning’, taken from Buddha’s Fire Sermon where he preached the abandonment of the fires of bodily cravings and lust, and is followed by St. Augustine’s plea to God to ‘pluckest me out’ [of the fire] from Book X of Confessions.

The same theme of asceticism returns at the end of the poem, with its evocations of the second Hindu Brahmana: ‘Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata’ [Give. Sympathise. Control]. This is widely interpreted as Eliot’s prescription for countering the trauma, disorder and chaos that followed World War I. The Sanskrit word for peace, ‘Shantih’ is then repeated three times to conclude the poem, and the film juxtaposes these words with footage of worshippers lighting tall candles at a Buddhist temple in Penang, Malaysia, and a bird flying in slow motion over the sacred mountain Agung in Bali – the abode of the island’s Hindu Gods.

The film counterpoints many of the poem’s sequences with images from the sculptural dioramas at Haw Par Villa in Singapore, created in 1937, which depict surreal and extraordinary interpretations of stories from Asian (and particularly Chinese) literature, myths, philosophy and religion. Its multitude of life-size statues provide a perfect complement to Eliot’s allusions to Eastern folklore and beliefs, and since many of these dramatic dioramas are partly broken or decomposing, they resonate with the poem’s darker message that cities, traditions and cultures are crumbling. [Figure 3]

Figure 3: ‘the nymphs are departed …’ One of the many Haw Par Villa dioramas used in the film.

There are so many locations and narratives within The Waste Land that the cultural park’s 1,000 statues and 150 group dioramas proved a blessing in terms of providing rich and affecting imagery to help evoke or illustrate them. Statues of two women seducing a priest at prayer are used against the lines: ‘The awful daring of a moment’s surrender / Which an age of prudence can never retract’; a statue of a warrior with a sadistically grotesque grimace counterpoints ‘The rattle of the bones, and chuckle spread from ear to ear’; while images of waving mermaids and sirens accompany the allusions to Rhinemaidens and the repeated phrase ‘the nymphs are departed’. Haw Par Villa has a number of dioramas depicting drowning, a key theme of the poem, including an elaborate shipwreck with victims also being eaten by sharks, which was used alongside Madame Sosostris’ ominous warning to ‘Fear death by water’. [Figure 4]

Figure 4: ‘Fear death by water …’ A vivid and gory shipwreck diorama visually accompanies Madame Sosostris’ grim prediction.

Awash with water

The poem has 3,022 words and 18 of them are ‘water’ – it the single most used noun in the work. Additionally, there are 6 references to rain, 5 to seas, 3 to rivers, 3 to fishing, 2 to wet, 2 to drowning, 1 canal, 1 spring and 1 shower. The work is a veritable ode to water. While a lack of it may lie at the heart of The Waste Land, its destructive effect turning land into barren desert, it is water rather than aridity that is the predominant, indeed obsessive theme.

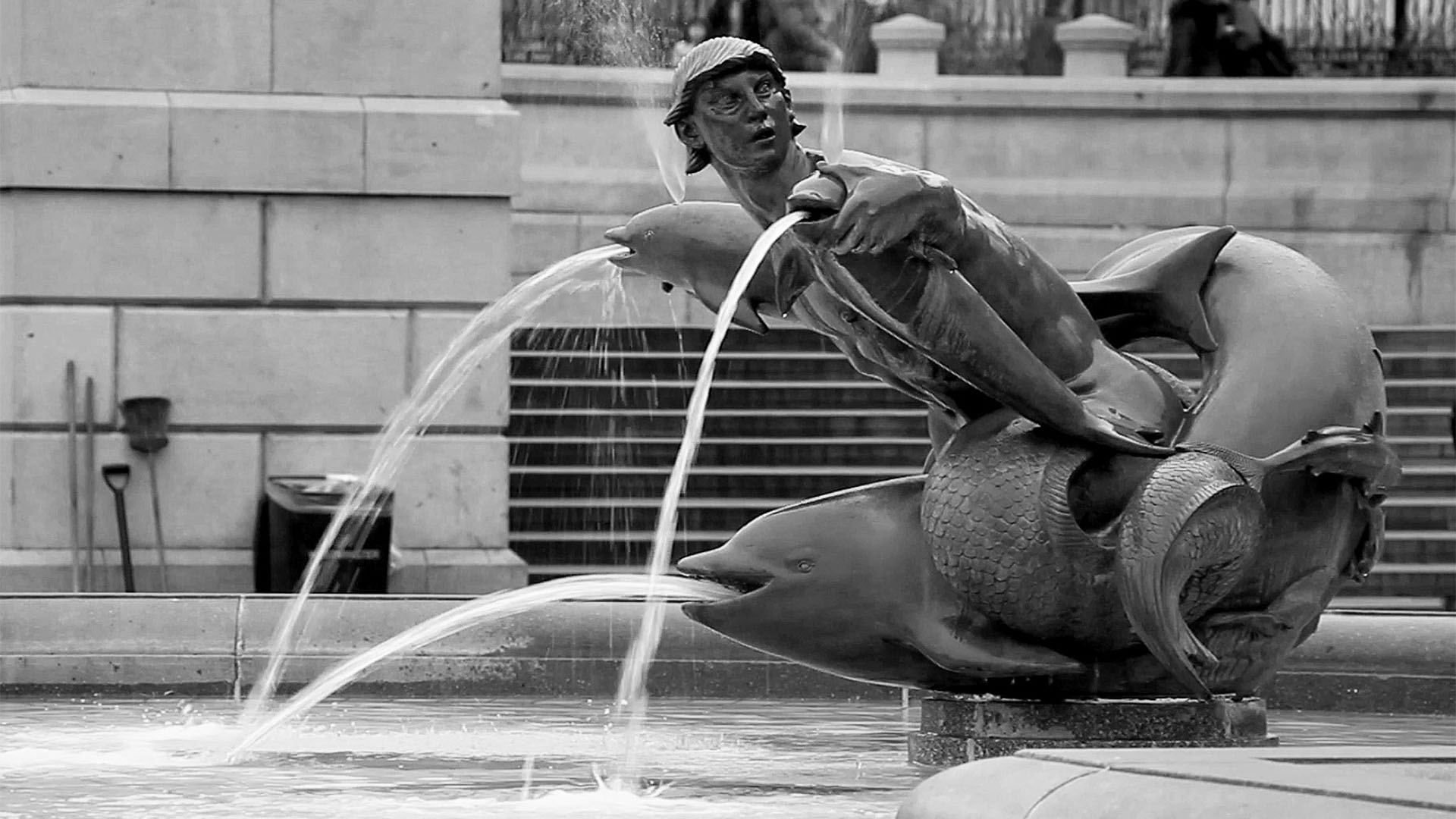

Revisiting T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land reflects this in myriad water sequences including extensive imagery of London’s River Thames: from closeups of sunlight shimmering delicately and beautifully in its watery ‘Inexplicable splendour’ to revealing how its surface palpably ‘sweats oil and tar’ pollutants. Vietnamese fishermen and women in traditional conical hats drag their nets, peacefully ‘fishing by the old canal’, and hundreds of cawing seagulls eddy above, and occasionally plunge down into the sea for fish as ‘the boat responded / Gaily, to the hand expert with sail and oar’. The tragic, impotent figure of the Fisher King is invoked using a Haw Par Villa statue of a bearded man whose entire body is encased in a full-length fish costume, with only his face peering out. For the ‘Death by Water’ section, the character of Phlebas is depicted by the statue of a heroic looking young merman riding a dolphin and holding onto other dolphins with each hand, while all three spit long jets of water into a fountain in London’s Trafalgar Square. [Figure 5]

Figure 5: ‘Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.’ An aquatic fountain statue in Trafalgar Square.

Water is a complex and polysemic element in The Waste Land: creative and destructive, life-giving and life-taking. It shares much with the poem’s other elemental theme, fire – both able to overcome and cross boundaries, to purify and to destroy. Water simultaneously signifies the cyclical, mortal nature of human existence, and the human quest to find meaning and spiritual regeneration in an unreal and hostile world. The poem’s continual allusions to water, including references to the Biblical story of captive Israelites weeping by the rivers of Babylon (Psalm 137) and the holy Indian river, the Ganges, being dried up and waiting for rain, relate to the themes of purification, spiritual enrichment and rebirth that our contemporary troubled world is perhaps as much in need of today as it was when Eliot wrote the poem. As K Thomas Baby (2018) observes: ‘Water is not only a social, cultural and religious symbol but it is the essence of all life on earth. It is sublime and destructive at the same time and embodies the principle of life, death and regeneration in itself.’

Following Eliot’s lead and spirit

Since the translational choices open to our production were so wide and free, a decision was made to keep as faithful as possible to the spirit of Eliot’s writing, but not necessarily follow every idea, narrative or allusion directly or literally. This enabled the creation of a free-flowing and associative translation with a contemporary scope and edge. For example, slow-motion footage of a bustling, densely packed Singapore shopping mall accompanies one of the several references to an ‘Unreal City’, while today’s skyscraper-lined Hong Kong harbour is employed to reflect the grandeur of historic ‘Alexandria’. Eliot’s plethora of religious allusions, from Buddhism to Christianity prompted filming of diverse religious sites, for example an ancient church mosaic of Jesus for the ‘He who is living is now dead’ section.

But such footage was not always used in direct correlation with a textual referent, and was rather added fluidly and accumulatively to reinforce the spirit of the poem’s religious plurality. For example, for the ‘each in his prison / Thinking of the key’ stanza, a pair of feet walk slowly across the floor of the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque in Istanbul, Turkey, emerging in and out of view amidst dark shadows cast by its giant windows. [Figure 6] Thus, the fragmented mosaics of the poem’s different stories and philosophies that span centuries from ancient to modern and continents from Europe to Asia, are doubled and reinforced in the filmic translation.

Figure 6: ‘We think of the key, each in his prison / Thinking of the key …’ A woman walks through the shadows in Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque.

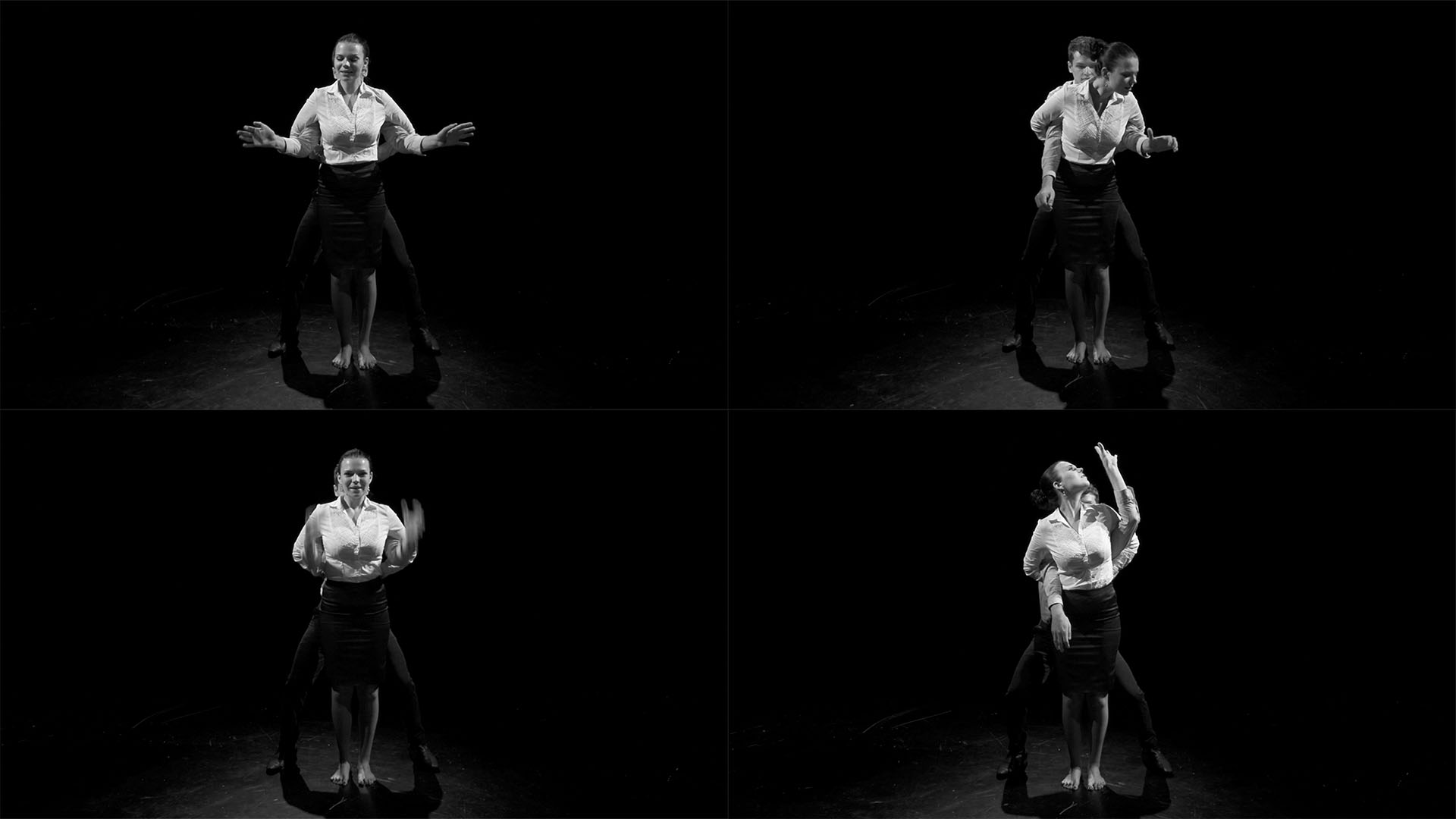

Following Eliot’s comment that he felt all the poem’s female characters are essentially ‘one woman’, the same actor, Kristina Pakhomova, was cast in all the female roles. She plays a nervously breathless and lovestruck Hyacinth Girl, an eccentric and intense Madame Sosostris, and a contemporary version of Shakespeare’s Cleopatra in the form of a posing, voguing model, for the opening of The Game of Chess section. Her role as the Typist is highly theatricalised, set within a bare, black-box theatre with the actor playing the ‘young man carbuncular’ operating her like a puppet, while an actor playing Tiresias watches on and comments sternly like a Greek chorus: ‘And I Tiresias have foresuffered all / Enacted on this same divan or bed. [Figure 7]

Figure 7: ‘The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights / her stove, and lays out food in tins. / … touched by the suns last rays’ From behind the typist (Kristina Pakhomova), the arms of the young man (Mitchell Lagos) theatrically mime each of her various actions.

A spirit of theatricality

The aim was to emphasise the marked theatricality and performativity of the poem, and some dramatic (or poetic) license was adopted to use the onscreen figure of Tiresias as a polyvocal lyric speaker and default narrator (doubling as the Fisher King near the end) to provide a conceptual through line. This conforms with the view of Calvin Bedient, who argues in his book (pointedly subtitled The Waste Land and Its Protagonist) that the various voices are the performance of a single character. Eliot, he says, is striving for ‘a self-transcendence attained by both a self-forgetting hero and a self-forgetting art’ (1986: 221).

Emily Hale, Eliot’s muse and inspiration for the Hyacinth Girl was an actress and theatre director to whom he wrote over a thousand letters. In 1935, Eliot told her the reason he turned to writing dramas was to impress her and provide her with characters to play (Dickey 2022: 3-4), and since he first fell in love with her in 1913, one might assume that nine years later, although a long time before his playwriting began, he was also flexing his theatrical muscles with The Waste Land. James Stayer analyses the poem’s over-emotionalism and what he calls its ‘groveling anguish … and embarrassing cri de coeur’ (2022: 147). To the French descriptors I would add the term coup de théâtre, since the poem reaches moments of intense and elevated theatricality, and our film seeks to capture this sense of high drama and actorly vocal address. [Figure 8]

Figure 8: ‘Who is the third who walks always beside you?’ A theatricalisation of the poem’s allusions to the Biblical resurrection, with three superimposed images of Tiresias (Steve Dixon) walking together through the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin.

- S. Pritchett called Eliot ‘a company of actors within one suit’, who was personally adept at playing everything from ‘the young dandy’ to ‘the religious mystic’ (cited in Thomas 1987). In translating the poem, we were conscious of highlighting this important part of Eliot’s personality and spirit at that time, and bringing the poem’s characters to life with a sense of overt performativity, even to the extent of emphasising theatrical artifice rather than a realist film style. The poem’s original title was taken from a line from Charles Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend, ‘He Do The Police in Different Voices’, and its quick-fire changes of voice, character and register are echoed in the film. This includes the fragmenting and splitting up of lines of text, which are delivered by the different voices of actors and their characters on, and sometimes off, screen.

The concrète music of poetry

Another key element of our translation which also followed Eliot’s lead was the composition of an atmospheric and densely layered sound design. While poetry generally shares much in common with music (tempos, rhythms, dynamics), The Waste Land is one of the most musically expressive ever written: a polyrhythmic and polyphonic tone poem with a symphonic structure and numerous leitmotifs. It has ‘an insistent stress on music’ (Rainey 2005: 42), quoting directly from operas and songs, and with its rhythms and musical sonorities plainly foregrounded. Eliot was fascinated by the musical and sonic aspects of poetry, which he highlighted in the very titles of his poems from his early Preludes to his final Four Quartets, and discussed in his 1942 article ‘The Music of Poetry’ where he describes a ‘musical poem’ as having ‘a musical pattern of sound and a musical pattern of the secondary meaning of the words which compose it, and … those two patterns are indissoluble and one” (quoted in Chancellor 1969: 22).

The award-winning Singaporean composer, Joyce Beetuan Koh, undertook a sonic analysis of the poem as the first step in conceiving an adventurous soundtrack. It provides direct responses to the poem’s ideas, images and rhythms; and amplifies its narrative and psychological elements. While drawing on the poem’s explicit references to musical styles such as ragtime and to operas such as Wagner’s Das Rhinegold and Tristan and Isolde, it particularly uses a musique concrète methodology. This is a sonic form using recordings of real sounds – from nature as well as from the urban environments and industrial settings – rather than traditional instruments. For the film’s audio design, these verité sounds are combined with processed electronic and synthesised effects. For example, in the sequence beginning ‘If there were water / And no rock’ and ending ‘But there is no water’ the sound design segues through three types of natural sound: water pouring out from a spring; water cascading into a subterranean cave (and its echoes), and finally the close-up sound of a single drop of water, whose reverberations are progressively electronically treated to intensify the climactic effect.

The section beginning ‘What is the City over the mountains’ features the sounds of real birds combined with synthesised zipping sounds that violently accent the visual movements of the footage of birds which dart across the screen to the words ‘Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air’. The audio then metamorphoses back into concrete sounds of real flapping wings as the names of cities are read out: ‘Jerusalem. Athens. Alexandria’. Human whispers take over, which are gradually electronically processed to accelerate and change pitch alongside the narration ‘And bats with baby faces in the violet light / Whistled and beat their wings’. Concrete sounds return with a fanfare of pealing church bells as the Chapel [Perilous] is revealed to the words ‘Tolling reminiscent bells, that kept the hours’, with the film showing a curtain being drawn open to dramatically reveal an old London church surrounded by blackened caryatids.

Sounds of real pigeons take over, that are gradually amplified to unsettling, menacing effect, with the sonic treatment heightening the textual themes of dryness, death and decay: ‘There is the empty chapel, only the wind’s home’. The sequence concludes with the image of a cockerel, whose morning call announces a rainstorm. Its staccato squawks and flapping wings are slowed down and electronically treated, becoming harsher and increasingly percussive, as two cockerels onscreen begin to jump at one another and fight, whereupon the wing sounds segue into thunderclaps: ‘Co co rico co co rico / In a flash of lightning’.

Conclusion: cooperating not competing

I began by noting that while all translators face myriad choices, they are expanded greatly and in different ways when translating a text into a film. They are seemingly infinite in the case of The Waste Land, with its multiple narratives and dense array of literary, cultural and religious allusions. Peter Wollen (1969) has argued that a film’s greatness is proportional to its wealth of connotations, and I hope that our translational choices serve at least to demonstrate the vast wealth of ideas, images and allusions Eliot conjures in the poem. [Figure 9]

Figure 9: ‘Fishing, with the arid shore behind me / … London bridge is falling down’ An image of a fisherman at sunset in Hoi An, Vietnam slowly cross-fades into an image of London’s river Thames and the ‘arid shore behind’ of its surrounding buildings including St Paul’s cathedral (centre).

The poem’s translation into the film Revisiting T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land aims to echo and evoke the general spirit of the work, though it could never hope to encapsulate all of its nuances and elements, nor express all the direct intentions of its writer. The ontology of the celebrated text was changed fundamentally, but most of its core narratives, characters, allusions, social critiques and cultural and philosophical musings remained, albeit expressed in a quite different audio-visual form. The task of translating the poem into film was a type of ‘comparative literature’ exercise, involving a transposition based on comparing, interpreting and balancing it in relation to the different languages and linguistics of film genres, theatrical conceits, image ideation, sound design and editing strategies.

In many way this mirrored Eliot’s own innovative approach in freely juxtaposing the old with the new, lyric poetry with narrative structures, and in fusing voices from high and low culture. He interweaves multiple styles, and shifts genres in the blink of an eye, dramatically and provocatively. As Hillis J. Miller points out, the poem centres on ‘abrupt juxtaposition. … The meaning emerges from the clash of adjacent images …The poem works like those children’s puzzles … when numbered dots are connected in sequence” (1965: 145); while Jennifer Emery-Peck calls it:

a narrative performance crisscrossed by class, gender, and intensified readerly desires. … a realm bristling with story-telling, with the voices of women and of working-class figures, with popular culture, with narrative techniques, and with the desires and techniques of a mass-reading audience. (2008: 331-332)

Mass-reading in the 1920s was generally confined to text, whereas screen media is today’s most favoured form. Since the poem’s very structure centres on the criss-crossing of disparate narratives and genres, perhaps the crossing of one more boundary to translate it into another medium is not quite as radical as might first appear. Its publication in 1922 (alongside Joyce’s Ulysses the same year) announced the advent of the modernist avant-garde in literature with a shocking and polyphonous fanfare. The Waste Land had already torn up the rule book of what Fredric Jameson calls the ‘literary institutions or social contracts’ of genre ‘between a writer and a specific public’ (1981: 106, emphasis in original), therefore translating it into another ontological form does not seem like too giant a step, particularly since Eliot was already consciously and fundamentally ‘Do[ing] the Police in Different Voices’. Emery-Peck argues that in The Waste Land ‘genres cooperate rather than compete’ and perhaps the same is true of forms, when transposing it from a literary to a media ‘text’. Paul Chancellor suggests it is a poem ‘in which two dreams cross – a dream in words and a dream in music” (1969: 21) and the transposition to film adds an audio-visual third element to the heady dreamscape.

Over a hundred years on, The Waste Land retains an immense power, and I hope this film may help open it up to new audiences and particularly younger readers. I also hope it underlines the poem’s currency and potency for our own time. The Waste Land grapples with themes that echo uncannily with the anxieties of today – from feelings of melancholy, loss and longing to the fear of death and the promise of renewal and rebirth. No matter in which form the work is translated, its powerful spirit, rhythms and messages endure, and as Edmund Wilson Jr observed in his oft-quoted review in The Dial of December 1922, ‘Mr Eliot is a poet … [and] no matter within what walls he lives, he belongs to the divine company.’

References

Baby, Thomas (2018) The role and significance of water in Eliot’s Wasteland. International Conference on Aquatic Literature, Alleppy, Kerala, India. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324279691_The_role_and_significance_of_water_in_Eliot’s_Wasteland

Bedient, Calvin (1986) He Do the Police In Different Voices: The Waste Land and Its Protagonist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chancellor, Paul (1969). ‘The Music of “The Waste Land”’. Comparative Literature Studies, Vol. 6, No. 1, 21-32.

Dickey, Frances. (2022). ‘Preface’. The T. S. Eliot Studies Annual, Vol. 4 Issue 1, pp. 1-5.

Emery-Peck, Jennifer Sorensen (2008). ‘Tom and Vivien Eliot Do Narrative in Different Voices: Mixing Genres in The Waste Land‘s Pub.’ Narrative, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 331-358.

Jameson, Fredric (1981). The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Miller, Hillis J. (1965) Poets of Reality: Six Twentieth Century Writers. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Rainey, Lawrence (2005). Revisiting the Waste Land. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Stayer, Jayme (2022). ‘Snuggling up to the Abyss’. The T. S. Eliot Studies Annual, Vol. 4 Issue 1, pp. 145-159.

Thomas, David [director] (1987) Ten Great Writers of the Western World: T. S. Eliot. Television programme. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UoEHySQ9Gmo&t=32s

Wilson, Edmund Jr (1922). ‘The Poetry of Drouth’. The Dial, Vol. LLXIII No. 6, December. pp. 611-616.

Wollen, Peter (1969). Signs and Meaning in the Cinema. London: Bloomsbury.

Steve Dixon is President of Lasalle College of the Arts, Singapore, and an interdisciplinary artist working in film, theatre, interactive media and installation. His film and digital works have screened at festivals including Leeds International Film Festival (UK), Moscow International Film Festival, and the New York Expo, and have won a number of awards including Best Experimental Film and Best Art Video. He is author of an award-winning 800-page history of technology in theatre and dance, Digital Performance (MIT Press 2007) and his latest book Cybernetic-Existentialism (Routledge 2020) fuses ideas from philosophy and systems sciences.

Une réflexion sur « Ontological conundrums: translating The Waste Land into a film »

Les commentaires sont fermés.