HÉLÈNE AJI

Abstract

Following on observations on obscenity in Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s works, this article successively examines poems, and essays by Ezra Pound to show how the obscenity of war, and of the Great War in particular, is a trigger for a psychotic decompensation of both personal and collective delusions, a process that after a paroxystic moment of crystallization contaminates both his life and his work. It generates “fables of aggression” in the words of Fredric Jameson about Wyndham Lewis, or the critique of society and the economy that Tim Redman sees unfolding in Ezra Pound’s “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley” as early as 1917 with the persona of E.P. and its pathological morbidity. According to Redman’s analysis of Pound’s turn to fascism, “so much of […] Pound’s transformation in thought is directly attributable to the shattering experience of the war”, so that one can trace the genesis of this “emotional reaction” in the work of Ezra Pound. At this historical turning point of the Great War, the obscenity of war implies both senses of the word’s etymology: ill-omened and abominable (or abject), the war becomes the event that entails a contradictory response, a divorce from the reality of the world that gives way to disconnected discourses of remediation and idealization, and a melancholic persistence in the moment of demystification and resignation from this world.

Résumé

Dans le silage d’observations faites sur l’obscénité chez louis-Ferdinand Céline, cet article examine des poèmes et essais d’Ezra Pound afin de montrer comment l’obscénité de la guerre, et de la Grande Guerre en particulier, déclenche la décompensation psychotique d’illusions personnelles et collectives, un processus, qui, après un temps de cristallisation paroxiystique, contamine la vie et l’œuvre. Il produit des « fables de l’agression », pour reprendre les mots de Fredric Jameson à propos de Wyndham Lewis, une critique de la société et de l’économie que Tim Redan voit se déployer dès 1917 dans « Hugh Selwyn Mauberley » d’Ezra Pound avec la persona d’E.P. et sa morbidité pathologique. Selon l’analyse que fait Redman du virage fasciste d’Ezra Pound, « une large part de la transformation de la pensée de Pound est directement liée à l’expérience fracassante de la guerre », de sorte que l’on peut suivre la trace de cette « réaction émotionnelle » dans toute son œuvre. À ce tournant historique de la Grande Guerre, l’obscénité de la guerre s’exprime dans les deux sens étymologiques du terme : néfaste et abominable (ou abjecte), la guerre devient l’événement qui provoque une réaction contradictoire, une dissociation de la réalité du monde qui engendre des discours déconnectés de remédiation et d’idéalisation ainsi qu’une persistance mélancolique dans un présent de démystification et de retrait de ce monde.

Keywords

Ezra Pound, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, American poetry, The Cantos, Fascism, The Great War or WWI

_______________________

In the “Carnet du cuirassier Destouches”, Louis-Ferdinand Céline writes:

51) un fond de tristesse est au fond de moi-même et si je n’ai pas le courage de le chasser par une occupation quelconque il prend bientôt des proportions énormes

53) au point que cette mélancolie profonde ne tarde pas à recouvrir tous mes ennuis et se fond en eux pour me torturer en mon fond intérieur. (Céline123)

Sadness, melancholy, and torture are the key words of a few lines that detract from the general impression one has of his writings, their violence, their use of slang to the limits of intelligibility, and above all the ideological options that make them entirely unacceptable in a vast number of instances. In Céline, Philippe Sollers attempts, against all odds and very often in ways that fail to come to any kind of resolution, to redeem Céline’s antisemitism through the fascination exerted by his literary talent, and his commitment to the reinvigoration of the French language: “Céline engage contre le diable une lutte à mort pour conserver la musique de sa langue” (Sollers 11).

Le tragique, pour Céline, est que cette langue en voie de disparition traduit, dans le renoncement et la résignation, la volonté suicidaire d’un peuple. […] Si bien que pour obtenir « le rendu émotif intime », seule façon d’écrire en français selon Céline, mais pour combien de temps, outre le labeur accablant, il faut traiter l’Histoire en direct, se refuser aux romans historiques insignifiants, aux romans naturalistes arriérés dont les Français se bourrent. (Sollers 13)

What Sollers’s analysis does not fully confront, however, is precisely the nature of the historical event that condemns all those works to insignificance, the major discrepancy between the capabilities of language and the actuality of experience, that makes previous modes not only outdated but radically defective. Do we actually want to redeem Céline as Sollers repeatedly in his essays constructs him as a scapegoat whereby a community tries to atone for sins it keeps committing? Or rather do we want to face the obsenity of Céline’s discourse as the testimony to the inspeakable horror of actions that cannot be collectively disowned?

In Pouvoirs de l’horreur, Julia Kristeva also devotes pages to Céline, as she examines the possible causes of the readership’s fascination for the work. Céline’s words function as catalysts or revealers of a place we refuse to travel, both inside and outside ourselves, which is made of inversions and perversions:

La lecture de Céline nous saisit en ce lieu fragile de notre subjectivité où nos défenses écroulées dévoilent, sous les apparences d’un château-fort, une peau écorchée : ni dedans ni dehors, l’extérieur blessant se renversant en dedans abominable, la guerre côtoyant la pourriture, alors que la rigidité sociale et familiale, faux masque, s’écroule dans l’abomination bien-aimée d’un vice innocent. Univers de frontières, de bascules, d’identités fragiles et confondues, errances du sujet et de ses objets, peurs et combats, abjections et lyrismes. A la charnière du social et de l’asocial, du familial et du délinquant, du féminin et du masculin, de la tendresse et du meurtre. (Kristeva 1980, 159)

What makes his writing so compelling is that it actualizes what she calls “ a black explosion” (159) that fails to reorder the organization it destroys, and performs the “apocalyptic collapse” which is the paroxystic instance of “a technique that is a way of being” (161-162). If we return to some works, Céline’s being most certainly the most radical, it is because they lay out in front of us the failure of rationality to grasp the mechanisms of their fascination and repulsion, as well as the potency of these mechanisms. Kristeva sets a tall task to the analyst as they are themselves caught in what she calls the “braid” (“tresse”) of abjection:

L’analyste, puisqu’il interprète, est sans doute parmi les rares témoins modernes du fait que nous dansons sur un volcan. Qu’il y puise sa jouissance perverse, soit ; à condition qu’il fasse éclater, en sa qualité d’homme ou de femme sans qualité, la logique la plus enfouie de nos angoisses et de nos haines. Pourra-t-il alors radiographier l’horreur sans en capitaliser le pouvoir ? Exhiber l’abject sans se confondre avec lui ?

Probablement pas. (Kristeva 1980, 247)

This is most probably the foundation on which any study of the genesis of many poets’ vision of the decay, and shipwreck of civilization can be built. The disgust for society, community, and the violence of descriptions of their decadence, are projections of a disgust from which the self cannot abstract, or substract itself.

No one is innocent of the “crime” which they wish to ascribe to “modernity,” in the words of Jean-Michel Rabaté, and the Great War plays a specific historical part in the recognition of this collective crime, so that our world, and its artefacts can be read as the elements of a “crime scene”. As he studies the emergence and the consequences of André Breton’s 1918 text entitled “Sujet”, Rabaté locates in the interwar years a turning point of the arts and literature that can be ascribed to a process of rejection and abjection defamiliarizing and de-realizing the world that surrounds us, as too horrible to be real. As Rabaté explains, “Sujet” is the transcription of the psychotic delirium of a traumatized soldier Breton met by chance in Saint-Dizier (Rabaté 240):

Il s’agissait d’un soldat traumatisé par le combat qui, en conséquence, avait cessé de croire à la réalité de la guerre. Pour ce patient, la seule manière de survivre psychiquement avait été de croire que la guerre n’était qu’un immense simulacre. Pour lui, les champs ensanglantés, les ruines et les cadavres n’étaient qu’une illusion théâtrale manipulée par des forces occultes. […] Le mécanisme de l’interprétation psychotique du monde suit la logique la plus inattaquable : comment le spectacle de massacres d’humains à une telle échelle pourrait-il être croyable? […] Dans « Sujet », on découvre que le monde entier est devenu un simulacre délirant. (Rabaté 241-242)

According to Rabaté, a number of hystericizing responses to the horror postponed then induced the paranoid reading of this psychosis which reaches out from the specific instances of individuals to the collective mind. Their expression may reside in obscenity as we commonly understand it, the exhibition of unbelievable spectacles that petrify and/or precipitate the viewer into disbelief and outrage.

Yet it will be our contention here, as we trace the genesis of this psychosis in the work of Ezra Pound at this historical turning point of the Great War, that the obscene lies in the double sense of the word’s etymology: ill-omened and abominable (or abject), the war becomes the event that triggers a contradictory response, a divorce from the reality of the world that gives way to disconnected discourses of remediation and idealization, and a melancholic persistence in the moment of demystification and resignation from this world. To this effect, I would like first to take into consideration the evolution of Blast, a little magazine which Pound edited and which had two issues (one before the beginning of the war, the other right after the death of his friend sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brezska in 1915): the two issues, as their tone varies, and they reposition the aesthetic options of early 1914 in front of the war and its consequences, are symptomatic of the historical, and aesthetic turn, that entails a more explicit assessment of modernity as obscene. Secondly, the memoir to Gaudier composed by Pound and published in retrospect, builds what we could call a monument against this obscenity, a book in the guise of a memorial as much as a memoir, in keeping with the memorials that pervade France, and were key not in the preservation of peace (their initial intention) but as reminders of an abjection that fostered more violence and horror. This second moment will allow me to return to Pound’s poems and notably, in a “A Draft of XVI Cantos,” to Canto 16 as it weaves references to the war into a morbid web of significance. This composition pertains to a psychotic ideological reconstruction akin to the de-realization at work in the traumatized soldier’s psychosis: integrating the obscene spectacle of dehumanization, it cancels it through its narrativization, fictionalization, and thus fails to disempower it. Although against the war in intent, the discourse is derailed into a violence that can but lead to more destruction, and will resurface years after, in the 1950s. The cantos are built to “shore against ruin,” to pick up T.S. Eliot’s words, to oppose obscenity, but they in turn are obscene insofar as they are omens for an abominable future. The trajectory is well summarized by Hugh Kenner in The Pound Era:

Six weeks after Blast was published Europe was at war.

End of a Vortex, though it was 1919 before Pound fully realized this bitter fact. By then he had a theme to animate what was to have been the Vorticist epic and became instead a poem on vortices and their fate: shaping of characterizing energies, and the bellum perenne that dissipates them. (Kenner 247)

What will be outlined, then, is the advent of an “everlasting war,” that pathologically entwines the negativity of experience and the stridency of expression into the hermetic combine of obscene poems.

Blast: the black explosion

As is well known, Blast was a short-lived little magazine, mainly edited by Ezra Pound, and by Wyndham Lewis, as part of promoting Vorticism, a London-based alternative to Italian futurism, that took over some of its aesthetic options (notably the interest in geometrical form, and the fascination for movement and energy as elements to be integrated to the more static visual and literary arts). The name of the journal Blast was in itself reminiscent of these options, with the addition of an agonistic, or even belligerent overtone, as it explicitly referred to the aftermath of an explosion, its destructive and devastating power. As a theoretical imperative before any reconstruction of art, one found the transfer of an aesthetics of war and combat that the “blast” of the Vorticist bomb came to embody. The vivid pink cover, as has been remarked upon by many critics, was meant to draw attention, and to surprise. Monochromatic and geometrical it took over some of the new typographical habits but also rearranged them diagonally so as to lend dynamics to the static lay out of the journal.

And indeed if one looks at the various texts gathered in the journal, many of them take the form of manifestoes: a series of statements and injunctions towards the redefinition of the arts. Two texts function together as replications of similar choices in possibly different media: “Vortex Pound” and “Vortex Gaudier Brzeska.” They form a triptych with a third vortex, authored by Wyndham Lewis. In “Vortex Pound,” what is most remarkable is the commitment to modern technology, and the insistance on the arts’ adopting the “mechanics” of engines or “turbines” (Blast 153) The basic impulse comes from the refusal to persist in what is perceived as an overall inertia, the incapability of man to take his life into his own hands, to cease being the passive receiver of “impressions” to become an agent of expression or, in Pound’s words, direction (“DIRECTING,” [Blast 153]) . The goal of these assertions is obviously to undermine futurism, deemed to be a “dispersal” of energy (Blast 153), in favor of an aesthetics that would use the energy of the past, as it rushes into the present to significantly shape the future. Only a few months before the war, in our restropective glance, the emphasis on a perception of humanity as bogged in a quagmire of “spent” expressions and unable of actually expressing, with the power and « efficiency » of modernity (Blast 153).

The charge against futurism is in fact still more explicit in the second page of Pound’s “Vortex,” as he refines his definition into the very well-known concept of the “primary pigment” or the “primary form” (Blast 153) that reconstruct a classification of the arts overturning the then classical Hegelian hierarchy, and reinvesting the dynamics of the arts as reformulated by Walter Pater in Studies on the History of the Renaissance.

EVERY CONCEPT, EVERY EMOTION PRESENTS ITSELF TO THE VIVID CONSCIOUSNESS IN SOME PRIMARY FORM. IT BELONGS TO THE ART OF THIS FORM. IF SOUND, TO MUSIC; IF FORMED WORDS, TO LITERATURE; THE IMAGE TO POETRY; FORM TO DESIGN; COLOUR IN POSITION, TO PAINTING; FORM OR DESIGN IN THREE PLANES, to SCULPTURE; MOVEMENT TO THE DANCE OR TO THE RHYTHM OF MUSIC OR OF VERSES. (Blast 154)

Conceptual clarity however is probably not the main trait of this capitalized organization of the arts, that belongs more to a scream of protest against existing organizations than to the well-reflected and unemotional assessment of artistic practices and their relations to the data of perception and emotion. The “Vorticist” returns not to the primitive arts (as his interest in the arts of the primitives may suggest it) but to primitiveness in the arts, a basic and radical foundation that could be compared, to pick up on the metaphor of the bomb and the blast, to the charge concentrated into the explosive device. What we experience as art would then be indeed the blast from the explosion, and its power is meant to blow us off in a similar manner. In retrospect, one cannot but acknowledge to what extent this metaphorical trend might have seemed relevant, or at least opportune, at a time of purely theoretical invention, to become entirely unacceptable once the devastation of the blast had turned into the matter of common knowledge and direct experience. The obscenity of such discourse, entirely unapparent in the spring of 1914, will force gestures of cancellation and self-censorship in 1915.

The Gaudier Brzeska counterpart of Pound’s vortex is centered on sculpture, and if one reads the text looking out for its own modes of metaphorization to formulate the aesthetic project, one encounters even more violent phrases to describe the stakes of artistic creation. intrinsically defined as a hunter engaged in a “fight” for survival (“His livelihood depended on the hazards of the hunt,” [Blast 155]) and “superiority” (Blast 156), man is envisioned as capable of unleashing “brutal” “energy” (Blast 155). In Gaudier’s intention though, in this specific text, the brutality of energy is related to a determination to exist in the fullest sense of the term. The desire is to live “life in the absolute” (Blast 155) and to experience “the intensity of existence” (Blast 155) in such ways as permitting the revelation of the “truth of form” (Blast 155).

In what emerges, in actuality, as a more focused, condensed, and clarified statement, Gaudier points at the endgame of Vorticism in terms that tie it to an agonistic fascination. Life is redefined as tensed between the experience of an “incessant struggle” and the fiction of a “conscious superiority” (Blast 156), that would allow the “will” of the artist who has “mastered the elements” of nature (Blast 156) to rule over the world in full deliberateness and controlled performativity. The pure shapes of the geometrical projection potentially would impose themselves on the shapeless masses of disorganized existence through the effectiveness of the “vortex” that channels energy into efficiency to actualize civilization’s imperial “embrace” of the world (Blast 156). In retrospect again, the discourse does transpire as a component of, rather than a counter discourse to, the pervasive ideologies that would promote wars as the rightful wars of civilization against the forces of disorder. Modern civilization according to Pound or Gaudier certainly is not what we understand as industrialized modernity, and see as the main cause for the Great War, but its modes and methods are strikingly akin to it. The shock of the experience of the war, rooted in the physical and material confrontation to what actually happens in conditions of “incessant struggle” (Blast 156), is all the more of a “blast” as it casts a deadly light on the dead-end of agonistics as a mode for the promotion of the arts. What could be part of a metaphorical web to push aesthetic changes and innovations cannot but be re-read literally (Jean-Michel Rabaté would say psychotically or in a paranoid way) as a radical threat to the integrity of the human in all its dimensions.

Consequently the second and last issue of Blast can be considered as the stage on which the tragedy of this reversal comes to completion, seals the fate of the arts into abjection, and condemns their expressions to obscenity. The pink of the first cover is gone, as well as, one might notice, the dynamics of the slant inscription of the magazine’s title. The color is drab, the brownish tone of mud: the design by Wyndham Lewis mixes forms of what could be the buildings of the modern city with the sleek long lines of canons and bayonets, the latter further defining themselves into extensions of the arms of soldiers whose grim faces are drawn flush with the structures that consctrict and threaten to crush them. The engraving is beyond the recognition of human frailty as it enforces humanity’s dissolution into the mechanized world that destroys it. These designs are echoed in the art work that is presented inside the issue, as for instance with the engraving by Christopher Nevinson entitled “On the Way to the Trenches” (Blast War Number 89). This aesthetics quickly becomes the trademark of the Vorticists at war. The perception of no future, in contrast with the projection and shaping of the future that was at the core of the first issue’s valuation of energy, is stressed in the broken lines that belie any idea of the “direction” intimated by Pound in his initial vortex (Blast 155). It is also to be seen in the full stop that closes the date of publication in a fairly unusual use of punctuation (“15 July.” [Blast War Number Front Cover]), and in the refusal to actually number the issue: the “war number” is not a second issue of Blast, but remains unnumbered, signalling the threat to continuity and serialization, the risk of final interruption, and the singularity of crisis.

The urgency of the issue’s overall discourse, and the artists’ turn to more violent and brutal imagery to convey the shock are perceptible, remarkably, in “The Exploitation of Blood” by Wyndham Lewis (Blast War Number 24). To provoke outrage and revulsion in the reader, he resorts to the ghastly vision of war profiteers, washing their “very dirty linen” in the “sacred blood” of the “Soldier” (Blast War Number 24). Conceptualized and capitalized, the soldier in the war becomes a heroic figure of abjection, as he is the creation of a demented world, both loved and embodying the most detestable in this world. His “blood” is sacred in the strongest sense of the term: revered and feared, to be adored, and to be kept at a distance untouched and untouchable. Obscenely “us[ing] the blood of the Soldier for [their] daily domestic uses” (Blast War Number 24), some “Blackguard[s]” attack the aesthetic decisions of such as the Vorticists on the grounds of their bellicist, violent, brutal rhetorics, and it is this assimilation which Lewis is trying to counter, while unwillingly confirming it. Indeed he cannot conceal the unease which stems from the factuality of such analyses: what passed for a strategy to change the forms of art has suddenly backfired into the promotion of a violence that cannot be sustained as part and parcel of an artistic purpose. Although he acknowledges that “the War may affect Art deeply” (Blast War Number 24), he denies the fact that it may close some avenues of development in a forbidding manner by radically questioning any claims to find art’s origins in the bestiality of the “incessant struggle” for survival (Blast 156). He clings to the fiction that “Life after the War will be the same brilliant life as it was before the War” (Blast War Number 24), although the very way he phrases it is paradoxical and disorienting:

The art of to-day is a result of the life of to-day, of the appearance and vivacity of that life. Life after the War will be the same brilliant life as it was before the War––it’s appearance certainly not modified backwards.

The colour of granite would still be the same if every man in the world lay dead, water would form the same eddies and patterns and the spring would break forth in the same way. They [the soldiers] would not consider it at all reasonable to assert that their best aimed “direct” fire would alter the continuity of speculation that man had undertaken, and across which this war, like many other wars, has thrown its shadow, like an angry child’s. (Blast War Number 24)

How can life “after” be modified « backwards »? What is modified « backwards » is in fact life “before” as it is automatically reconsidered and reinterpreted as the life that led to the war. Usurping the soldiers’ voices and belittling the war as childish tantrum of customary intensity, Lewis fails to assess the epistemological turn that the war actually performs by cancelling the possibility of seeing aesthetic options as disconnected from the historical conditions of their emergence.

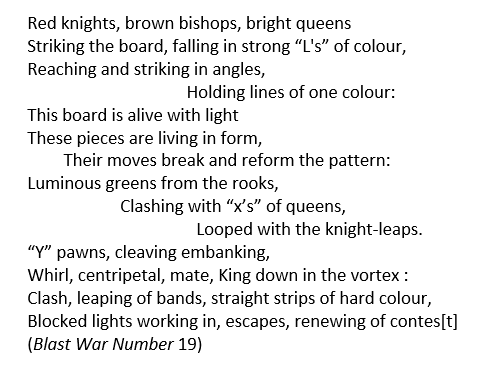

In this perspective, the publication in the same war issue of Ezra Pound’s “Dogmatic Statement on the Game and Play of Chess” (Blast War Number 19) cannot be confined to the reading the poet officially foregrounded.

This text is not merely a masterful example of the Vorticist poem as dynamic, playing on syntactic juxtaposition and the quick succession of images and colors to convey the speed of perceptions, and inscribe movement into the “primary pigment” of poetry that is language (Blast 155). This analysis does stand as one looks at the poem in terms of form and technique, but one cannot help but find the semantics, and the very choice of the game of chess disquieting in their appropriation of the rhetorics of war. It is no breaking news indeed that the game of chess is a war game of entrenched soldiers and threatened super powers that will not hesitate to sacrifice pawns in the name of their protection and victory. Nor is it difficult to trace in the words “striking,” “clash,” “blocked” or “contest” the signifiers of combat embedded in the text of the poem. In 1915, can “holding lines” or “embanking” fail to echo the realities of the trenches? And can one remain indifferent to the highjacking of these realities of destruction and death as positive metaphors to define the new art? They are the symptoms of two contradictory injunctions that are being enforced simultaneously: the ethical compulsion to embed the war in every speech act as it comes to inform perception as a whole; the deliberate and untenable decision to pursue the metaphorization of the new art as an art at war and of war.

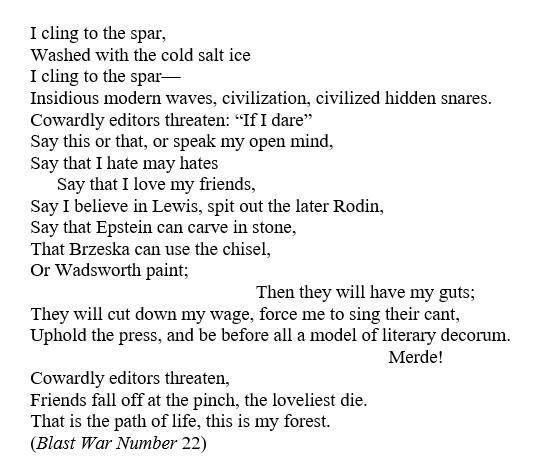

Similarly, the intertextuality of French medieval poet François Villon in another of Pound’s poems of the same war issue of Blast, “Et Faim Sallir le Loup des Boys” (22) ineluctably propels the reader out to the countryside of France, and the ravaged fields of the Somme, so pervasively present in the minds and conversations as to entirely eclipse the erudite reference to a more gentile medievalism.

This medieval Pound is one of the dark ages rather than the courtly love of Renaissance musings. The Dantean forest, which was fairly dark and forbidding already, is darker still as it fills with cannibalistic wolves. From being the instigator of machines that would formalize the scattered energies of a shapeless world, modernity rears its ugly head as “cowardly,” “insidious” and coercive. In 1915, in a significant manner, Pound’s exclamation “Merde!” summons the scatological into the poem, and initiates the obscene response to unspeakable crimes—Céline’s invective in Voyage au bout de la nuit is just around the corner. The cause of the breakdown is expressed in one line of tremendous pathetic import, which runs contrary to the antecedent clamors for impersonality and the banishment of affect from the poem: “Friends fall off at the pinch, the loveliest die” (Blast War Number 22). The caesura signs the rupture and discontinuity, the set phrase “at the pinch” in the middle of the line underscores the suddenness and contingency of experienced loss, the substitution of the superlative “the loveliest” for “friends” achieves the tragic generalization that turns the individual case into an emblem of collective experience. By becoming the abstract “loveliest,” the dead friend is this “boy” that stands for all the “boys” subliminally inscribed in the transcription from the old French in the poem’s title “Et Faim Sallir le Loup des Boys.”

The war number indeed revolves around the construction of this voice “from the trenches” which is a voice from the grave, and more generally from the massive graveyard that continental Europe has turned into. The second vortex by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (Blast War Number 33-34) is an instance of the heart-breaking letters from the front that fill the archives of the Great War, and the drawers of so many men and women at the time, at the same time as it is redolent of the agonistic delusions that had motivated the initial Vorticist manifestoes. Where energy allowed for a bragging assertive art manifesto in the first issue of Blast, it becomes the feeble spark that keeps a “small individual” barely alive, as we can read, but as the author deliriously denies.

I HAVE BEEN FIGHTING FOR TWO MONTHS and I can now gauge the intensity of Life.

HUMAN MASSES teem and move, are destroyed and crop up again.

HORSES are worn out in three weeks, die by the roadside.

DOGS wander, are destroyed, and others come along.

WITH ALL THE DESTRUCTION that works around us NOTHING IS CHANGES, EVEN SUPERFICIALLY. LIFE IS THE SAME STRENGTH, THE MOVING AGENT THAT PERMITS THE SMALL INDIVIDUAL TO ASSERT ITSELF. (Blast War Number 33)

The “intensity of life,” so valued and asserted in the first vortex, is no more the moving inner power of the individual that makes him create beauty but a cruel force of nature that pays no attention to the distressing spectacle of “human masses” to be “destroyed” and left by the side of the road like horses, dogs, or so many superfluous units in the overall count of a sustainable global economy. Gaudier recognizes that the conditions cancel “artistic emotions,” but despite the unspeakable horrors of this massacre the denial persists:

IT WOULD BE FOLLY TO SEEK ARTISTIC EMOTIONS AMID THESE LITTLE WORKS OF OURS.

THIS PALTRY MECHANISM, WHICH SERVES AS A PURGE TO OVER-NUMEROUS HUMANITY.

THIS WAR IS A GREAT REMEDY.

IN THE INDIVIDUAL IT KILLS ARROGANCE, SELF-ESTEEEM, PRIDE.

IT TAKES AWAY FROM THE MASSES NUMBERS UPON NUMBER OF UNIMPORTANT UNITS, WHOSE ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES BECOME NOXIOUS AS THE RECENT TRADE CRISES HAVE SHOWN US.

MY VIEWS ON SCULPTURE REMAIN ABSOLUTELY THE SAME. (Blast War Number 33)

And so does persist the claim that these circumstances do not change the options taken for art previously. The discourse on the absurdity of war fails to develop and morphs into a discourse of human expendability that one would hear again in Pound’s fascistic arguments on the superiority of geniuses, the necessity of their existence to the detriment of the insignificant existence of smaller men, the “Untermenschen” of German Nazi ideology in the 1930s and of American Aryan supremacy in the 1940s and 1950s. The focus on will and will power (“IT IS THE VORTEX OF WILL, OF DECISION, THAT BEGINS,” [Blast War Number 33]), Nietzschean in origin, pervasive in this text, as it is in Lewis’s attachment to a certain German culture (Blast War Number 24), or in Pound’s commitment to a prophetic dimension of the poet, emerges from the direct experience of the obscenity of war, and its immediate denial. Breton’s “sujet,” as analyzed by Rabaté, surfaces here too, as the sculptor de-realizes his own experience, and confuses the illness for a remedy: the battlefield of “Le sujet” has been turned by trauma and neurosis into this stage meant to wisen up the masses, as it has absurdly become, for Gaudier (and those who publish his prose), the locus for a collective cure.

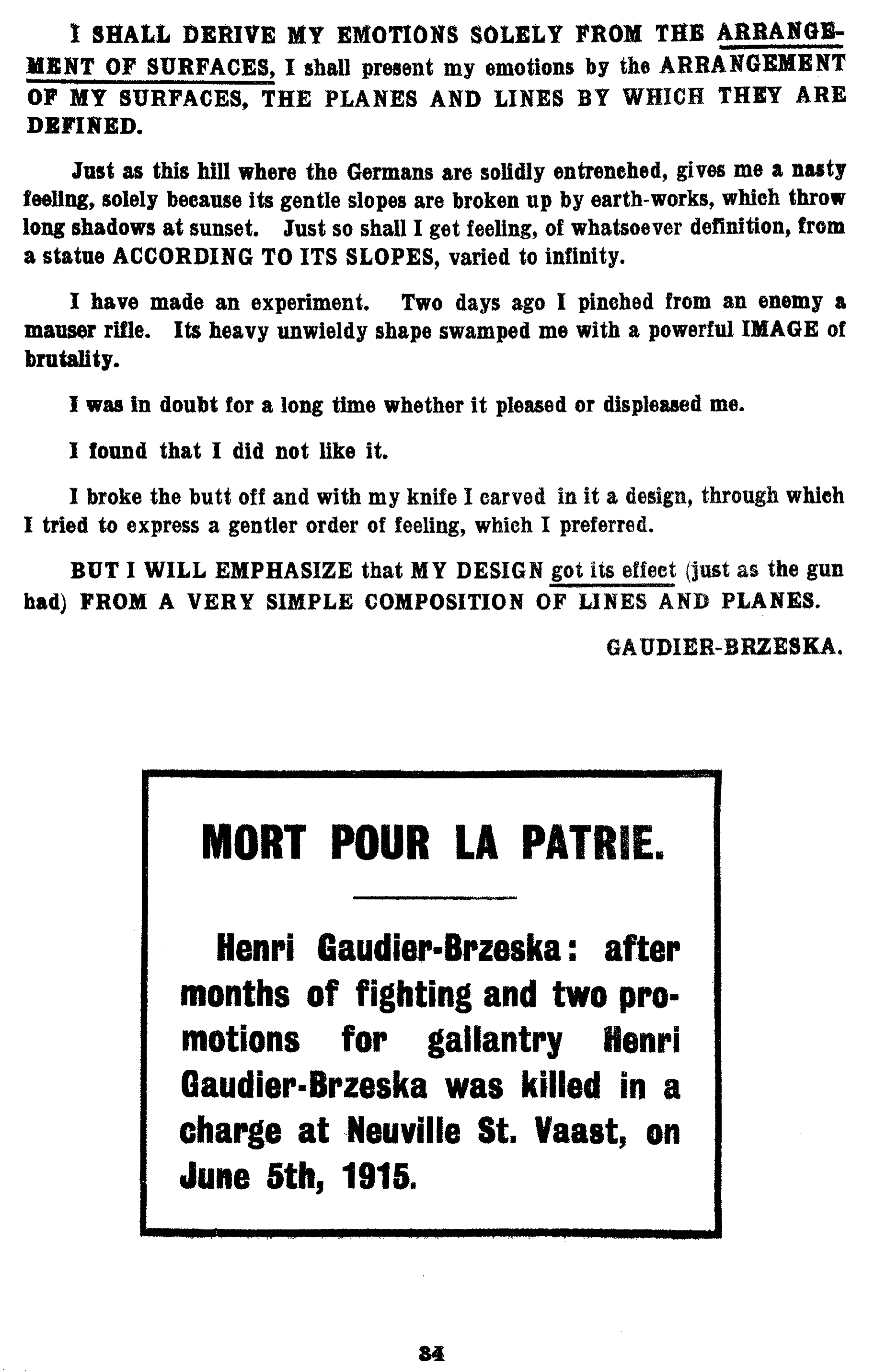

The second page of Gaudier’s vortex from the trenches provides a visual model for this perversity of the reaction to the war and the confusion in values and significations which it entails.

(Blast War Number 24)

The “hill” is a dangerous place whose lines are “broken” by trenches and bomb holes, but its geometrical forms remain the forms of art; the wood of the gun butt is not pleasant to the artist as part of a weapon, but once broken off it can be turned into an object of pleasure and beauty through crafting and carving into geometrical “lines” and “planes”; the last words of Gaudier’s text repeat the basic tenet for Vorticist aesthetics, the formula defined by T.E. Hulme, picked up by Ezra Pound, and turned into a somewhat ineffective, but highly symptomatic mantra. The sculptor himself evidences the refusal to connect the aesthetic decisions to their ideological consequences. A striking footnote to this explosive act of faith, the editors of the journal, Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis, underscore the young scuptor’s vital if paradoxical commitment to his art with the official announcement of his death which they have carefully composed into a geometrical imprint on the page. “Mort pour la patrie” does slightly diverge from the official phrasing though (“mort pour la France”), as does the alliance of the French in the heading, and the English in the explanation: as appropriated by Pound, and possibly but less markedly by Lewis, Gaudier’s death becomes the objective correlative of a personal, and collective hallucination, that would believe that the structures of war could be dissociated from the realities of war; that one could keep preparing for war and never fight it again; or that the detestation of war to the point of violence would not be as obscene as the images from the trenches, as ill-omened and abominable.

A memoir: the crime scene

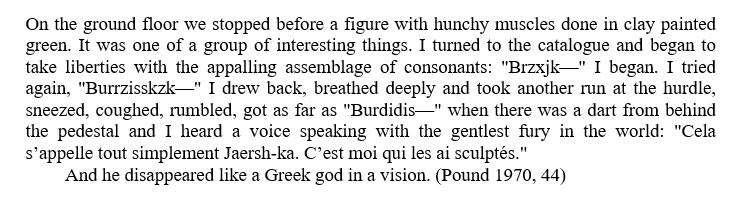

Thus Gaudier-Brzeska’s graveside, where his friends stand crying over the loss of the “loveliest” (Pound, Blast War Number 22) eludes the status of a place of mourning and recovery to become one of the “crime scenes” of “modernity” to return to Jean-Michel Rabaté’s words. Ezra Pound had met the young sculptor by pure chance at an exhibition at the Royal Albert Hall in London in July 1913. And this is how he describes the encounter in the memoir:

The very description of Gaudier’s intervention, as it is revisited after his death, confers him the quality of a supernatural being, he appears and disappears suddenly, he seems unreal, both violent and « gentle », a paradoxical creature that actually crystallizes the paradoxes he has come to embody in the poet’s mental construct. This design of the legend of Gaudier is notably exemplified in the various choices made by Pound for the editions of the memoir, including the latest edition published by New Directions under Pound’s supervision in 1970, as the poet looked back on a lifetime without his friend. The chosen illustration for the title page shows Gaudier “working on the Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound,” sculpting the shape of the poet’s head as he envisions it, literally creating the forms which the poet’s mind would to a large extent inhabit for the rest of his life. Symbolically, the sculptor stands as the maker of the poet’s head, potentially pointed out, in retrospect, as the force that would inflect the entirety of his thoughts. Similarly, the lay out of the adjoining page does not fully enlighten the reader as to whose memoir it is of whom, who is the author, who is the object of the book (and indeed the book gathers texts from Pound and from Gaudier). The names of the sculptor and of the poet are written in capital letters of the same size above and below a short title: A Memoir. One might venture that the two instances are on a structural level interchangeable and each the product of the other’s discourse. This interchangeability which makes Pound become Gaudier’s voice, and which turns Gaudier into the catalyst for Pound’s dejection and denial, finds its origins in the traumatic node of Gaudier’s death. The foreword, and the epigraphs that immediately follow (Pound 1970, 9) cast a different outlook on the significance of the memoir in Pound’s eyes, from the initial project of “emphasizing a few of Gaudier’s modes of work,” to a revaluation of the historical meaning of this work: the actuality of the work becomes a “footnote” to an alternative discourse. What is at stake is not just a “footnote” then despite the declaration in the foreword, but the main body of discourse that Gaudier’s death has allowed to produce. The book includes the memoir per se but reaches out more widely to cast a light on the whole of Pound’s production after the Great War, in all its perverse claims to beauty and exceptionality. By transfiguring Gaudier’s death, objectively in itself a footnote to the millions of dead in the war, into a key event to upset the world order, Pound substracts the collective dimension of the war to integrate it as a personal affront inflicted by all to the very few elect. Cattle instead of real men, in the Machiavelli quote at the bottom of the same page (“Gli uomini vivono in pochi e gli altri son pecorelle”), they do not deserve attention; real men are few, and the only ones to whom life is owed. Liminally, the poet lays down the foundation of his sacralization of Gaudier by performing the obscene gesture of lending greater import to the loss of one than to the massacre of millions.

Repeatedly though, as in the beginning of the 6th section of the memoir, Ezra Pound inadvertently recognizes the lack of rational foundation in what becomes a myth of anti-modernity. “My memory of the order of events from then on is rather confused,” he says (Pound 1970, 51), as if failing to recount Gaudier’s life in a chronological manner, or rather with the clarity that is associated with historical, or biographical enterprises. That may be because the enterprise is not aimed at producing more information about Gaudier (and indeed most of what one finds in the memoir is anecdotal). The intent is to fabricate a series of key moments, “luminous details” in Pound’s terminology, that recast the entire set of events, fictionalize them to utilize them as components for a alternative saga. Described further down as une “âme pure” (Pound 1970, 53), the Gaudier that emerges from the quagmire of the trenches, dead but also, if one may say, annointed in mud, this Gaudier is a modernist saint, an antidote to the contaminations of modernity, and not an emanation from this modernity that before the war was the motivation of the turn to geometry and dynamics. What the war produces is a complete reversal in Pound’s system of signification, one that is also an indicator of the inversion in his very conception of humanism.

In “Cantico del Sole,” a poem contemporary to the memoir, the incantation to the classics and what they could mean to America in 1920 wishes for the advent of an era that would pre-date the crime (or at least the event which is perceived as the crime), but it also underlines the delusion that lies in this wish, its impossibility.

The repetitivity points at the advent of obsession as the iterative summoning of the traumatic and attempt to overcome it. Coupled together, the two feed from one another, and construct the circle of non curative reneenactment, that prevents mourning and safe-guards the violence of the initial wound. The death of Gaudier is not to be overcome ever. At the end of section VI, Gaudier goes “back to his death” (Pound 1970, 54) as he returns to the front after having recovered from a wound: the phrase might seem innocuous at first reading but it conveys the radically thwarted causality that has come to inform Pound’s thought and consequently his writings. The manifestation of the dysfunction returns periodically, something visible in the 1970 edition of the memoir, as it gathers the introductions to all of the successive editions, and thus chronicles the circularity of impossible mourning. In 1918, Pound writes a first text for the memorial exhibition: Gaudier’s “death in action at Neuville St. Vaast is […] the gravest individual loss which the arts have sustained during the war” (Pound 1970, 136). In 1934, he writes a “postscript” to the edition, which opens with a renewed cry of despair: “For eighteen years the death of Henri Gaudier has been unremedied. […] The uncreated went with him” (Pound 1970, 140). As the death persists in its vividness, the perception of loss pervades not only the actual but the potential, transforming the poet’s world into a total memento of loss and absence. No sight is sightly any longer as everything is turned into a nauseating, negative, reminder of the missingness of the one. The famous “Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound,” although not Gaudier’s last work, remains in the eyes of the poet a “final manifestation” of what “the sculptor ‘sees’” that common men will never see, as he explains at the end of the description of the plates that illustrate the memoir (Pound 1970, 145). A masterful piece of art, and most probably one of Gaudier’s major pieces, Plate XIII in the memoir shows it on one side only (Pound 1970, 160), and no comment is made on its back, although it is where a discourse about Pound, and about the Vorticist project unfolds, but by 1918 this discourse has indeed become obscene in the more down-to-earth sense of the term. Shaped like an erect phallus, the hieratic head also speaks to the sexualized aggressiveness of Vorticism, and Pound’s promise, in Pavannes and Divagations, to rape “the great passive vulva of London” (Pound 1958, 204). The obscene image, and the obscene remark cannot hold after the war because this violence must be silenced. Silencing it gives it however more power to return and achieve the radical disconnection from the community of humans that would open the door to the stridencies of Fascism and anti-Semitism.

Canto 16 (1930) to Section: Rock-Drill De Los Cantares: black sun

In Soleil noir. Dépression et Mélancolie, Julia Kristeva analyses the psychiatric manifestations of melancholy, and depression, stressing the ambivalent relations between total apathy, and aphasia (that effectively prevent creativity), and active manifestations of the pathology (that are on the contrary productive, at times creative, and possess a high power of fascination, and persuasion). “La beauté [est] l’autre monde du dépressif” (Kristeva 107), and the quest for this beauty sets us in motion and fascinates us, in Pound’s case, but in Céline’s too, and Wyndham Lewis, or James Joyce, and the list of instances is indeed much longer. As a case in point, “Canto 16” takes the reader through familiar places and images with the confusing indeterminacy of a spatial and temporal collapse.

“Hell” and “hill” are interchangeable, as the Dantean hell of “Il Fiorentino” (Pound 1998, 68) merges with the nightmarish hills of the battlefront in France. The “howl[ing] against the evil” is doubled by an obstinacy to “gaze on the evil” (Pound 1998, 68) with a use of the definite article that foregrounds the specificity of this evil. But the howler and gazer is British mystical poet William Blake, and not the expected soldier witness. The transition-less movement between heterogeneous temporalities, places, characters, contributes at the same time to a defamiliarization that parallels the alienation of the traumatized, and to the assertion of a permanence of the horror.

“The criminal” is also the victim, as he lies in the “lakes of acid,” that a page further are a “lake of bodies” (Pound 1998, 69): the corpse is the corpus delicti, the object of the “crimen” becomes tantamount to its perpetrator.

The loss of “face” is both the ultimate desecration inflicted on the body, and the ultimate dishonor which has made it lose “face.” With its “face gone,” the body is obscenely disfigured and sinned against, and obscenely punished for its unspeakable sins. The intensity of the contradiction cannot but produce the escapist liberation into an abstract, suspended, timeless and placeless world that could be seen as a paradise:

Blue sky, light air, peaceful heroes, nymphs, and quietness characterize this city of fiction, which one could read as the equivalent (if inverted in its imagery) of Breton’s patient’s imaginary battlefield. Imaginary peace is as shocking as it attempts to cancel the ethical imperative of the horrified “gaze” (Pound 1998, 68). Be it only visually through the increasing proliferation of ellipses, the poem shows the symptoms of disruption, denial, and threatening silence, as the artificial paradise dissipates, and the images and tales of the horror crop back up to the surface of the text (Pound 1998, 70). The list of names, and accounts of friends gone to war, be they dead, wounded, or none of the above, happen as a radical revision of the impersonality and emotionlessness of pre-war Imagism and Vorticism. The war is personal, although it affects the whole of the community: lived on the level of the individual, it is inconceivable, and obscene because concrete and factual.

“They killed him,” about Gaudier-Brzeska pulls his death out of the realm of the acceptable by making this criminal “they” an indeterminate pronoun that does not choose its side among nations. What made the discourse of war audible, maybe, as a political event, is suppressed to insist on the general criminalization of all in war without consideration for the wider context. “They” is the criminal other that leaves the door open to more discourses of paranoia. In Pound’s discourse, the bestiality of war is highjacked to feed into a discourse of general, blind indictment. It becomes an argument to cast the blame on the other, on modernity, and on a devalued humanity, that is left exposed to contempt and insult. This canto contains two pages that make up its core: written in French they are stylistically very close to the writing of Céline at the same moment. The writing in the vernacular (“l’français, i s’bat quand y a mangé.” [Pound 1998, 73]), the focus on body function and the hint of necrophilia, the description of men as animals (“Les hommes de 34 ans à quatre pattes//qui criaient ‘maman.’” [Pound 1998, 72]) simultaneously state the humanistic claim against war and undermine humanism: the obscenity is corrosive insofar as it attacks what it tries to defend. True to the pattern of traumatic non-closure, the canto ends on an intimation of the eternal return of the same, an endless beginning postponed, which entraps both poet and reader:

The horror of the war is this “black sun” that Kristeva shows as shining negatively on the world of the clinically depressed, but it is magnified into a radical unnameable as it now shines on all alike, and converges with the human condition. And so it returns in the 1950s with “Section Rock-Drill de los Cantares,” which takes over the artefacts of war and reactivates them, most remarkably with the evocation of Jacob Epstein’s sculpture. Rock-Drill began as a plaster figure representing a worker using a rock-drill that had been integrated to the art work in ready-made fashion. As a close collaborator of the Vorticists, Epstein subscribed to the initial claims in favor of geometrical stylization and a glorification of the mechanical. The first version was broken, what remained of the plaster figure being used to prepare the casting of a metal version made out of gun metal from guns taken in the war from the Germans. The machine had emerged as an instrument of destruction, and was removed. However gun metal became constitutive of the work to point at the major transformation brought about by war to the human body itself. Cast in metal, the work is lasting, as is the damage done to the human body that loses a limb in the process, but gains the shape of a fetus ensconced between its ribs. The “generation” from Pound’s Canto 16 is one placed under the sign of war, and the torso of Rock-Drill stands out as the endangered place of its emergence.

Only a few months ago, the war was over again, and on November 11, 2018, the toll rang for eleven minutes from all the churches in France, and it was rainy and muddy on the vast necropolises of Northern France as it had been on the battlefields of a century before. In these necropolises, as their name indicates, the dead have their own city where they live forever in silent battles that are never-ending. It is but one of the obscene spectacles that are the black suns of the world. This world is the improbable child born from a deformed body of gun metal, as in the second version of Epstein’s Rock-Drill. And it may be the point where the poetry stops, or in Pound’s case where it could have stopped: in its stead, there rose an alternative noise, fascinating and threatening, from the silence of depression that Kristeva mentions at the beginning of Soleil noir whereby nonsense becomes “evident” and “unavoidable” (Kristeva 1987, 13). Pound’s texts after the Great War are fragmented by this temptation of silence, elliptical and allusive, bogged in disruptive unintelligible ideograms and signs, but they are also unwillingly spreading the seeds of destruction and disorder, as the only sense they manage to retrieve from the carnage and the rubble is to promote the redemption of humanity through self-hatred and its own annihilation. A paradise that is an inferno, and where one “cannot make it cohere” (Pound 1998, 816).

« Mais les cadavres, que doit-on en faire?” asks Jean-Michel Rabaté, since the shipwreck is not as Breton’s “sujet” believes, only in the mind: one option would be to “decide the death of civilization, to decide on how to make it happen” (Rabaté 289), an ultimate gesture of obscene self-cancellation and collective suicide.

Works cited

Céline, Louis-Ferndinand. Casse-Pipe, suivi du Carnet du cuirassier Destouches. Paris: Gallimard, Folio, 1952.

Kenner, Hugh. The Pound Era. London: Pimlico, 1991.

Kristeva, Julia. Pouvoirs de l’horreur. Paris: Seuil, Points, 1980.

Kristeva, Julia. Soleil noir. Dépression et mélancolie. Paris: Gallimard, Folio, 1987.

Pater, Walter. Studies in the History of the Renaissance. London: Macmillan, 1873.

Pound, Ezra. A Memoir of Gaudier-Brzeska. New York: New Directions, 1970.

Pound, Ezra. Collected Shorter Poems. London: Faber, 1984.

Pound, Ezra. Pavannes and Divagations. New York: New Directions, 1958.

Pound, Ezra. The Cantos. New York: New Directions, 1998.

Rabaté, Jean-Michel. Étants donnés: 1. L’art 2. Le crime–La modernité comme scène de crime. Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2010.

Sollers, Philippe. Céline. Paris: Editions Ecriture, 2009.

Une réflexion sur « Obscene Modernity: Ezra Pound against the Great War »

Les commentaires sont fermés.